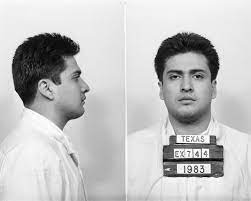

Carlos DeLuna was executed by the State of Texas for a murder committed during a robbery

According to court documents Carlos DeLuna would rob a gas station and in the process would shoot and kill the clerk Wanda Lopez

Carlos DeLuna would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death

Carlos DeLuna would be executed by lethal injection on December 7 1989

Since the execution of Carlos DeLuna it is believed that the police and courts are responsible for the execution of an innocent man. The true killer of Wanda Lopez is believed to be Carlos Hernández Jr who looked very similar to that of DeLuna. Hernandez Jr would die in prison in 1999

Carlos DeLuna Photos

Carlos DeLuna FAQ

When was Carlos DeLuna executed

Carlos DeLuna was executed on December 7 1989

How was Carlos DeLuna executed

Carlos DeLuna was executed by lethal injection

When did Carlos Hernández Jr die

Carlos Hernandez died in prison in 1999 from cirrhosis of the liver

Carlos DeLuna Case

A few years ago, Antonin Scalia, one of the nine justices on the US supreme court, made a bold statement. There has not been, he said, “a single case – not one – in which it is clear that a person was executed for a crime he did not commit. If such an event had occurred … the innocent’s name would be shouted from the rooftops.”

Scalia may have to eat his words. It is now clear that a person was executed for a crime he did not commit, and his name – Carlos DeLuna – is being shouted from the rooftops of the Columbia Human Rights Law Review. The august journal has cleared its entire spring edition, doubling its normal size to 436 pages, to carry an extraordinary investigation by a Columbia law school professor and his students.

The book sets out in precise and shocking detail how an innocent man was sent to his death on 8 December 1989, courtesy of the state of Texas. Los Tocayos Carlos: An Anatomy of a Wrongful Execution, is based on six years of intensive detective work by Professor James Liebman and 12 students.

Starting in 2004, they meticulously chased down every possible lead in the case, interviewing more than 100 witnesses, perusing about 900 pieces of source material and poring over crime scene photographs and legal documents that, when stacked, stand over 10ft high.

What they discovered stunned even Liebman, who, as an expert in America’s use of capital punishment, was well versed in its flaws. “It was a house of cards. We found that everything that could go wrong did go wrong,” he says.

Carlos DeLuna was arrested, aged 20, on 4 February 1983 for the brutal murder of a young woman, Wanda Lopez. She had been stabbed once through the left breast with an 8in lock-blade buck knife which had cut an artery causing her to bleed to death.

From the moment of his arrest until the day of his death by lethal injection six years later, DeLuna consistently protested he was innocent. He went further – he said that though he hadn’t committed the murder, he knew who had. He even named the culprit: a notoriously violent criminal called Carlos Hernandez.

The two Carloses were not just namesakes – or tocayos in Spanish, as referenced in the title of the Columbia book. They were the same height and weight, and looked so alike that they were sometimes mistaken for twins. When Carlos Hernandez’s lawyer saw pictures of the two men, he confused one for the other, as did DeLuna’s sister Rose.

At his 1983 trial, Carlos DeLuna told the jury that on the day of the murder he’d run into Hernandez, who he’d known for the previous five years. The two men, who both lived in the southern Texas town of Corpus Christi, stopped off at a bar. Hernandez went over to a gas station, the Shamrock, to buy something, and when he didn’t return DeLuna went over to see what was going on.

DeLuna told the jury that he saw Hernandez inside the Shamrock wrestling with a woman behind the counter. DeLuna said he was afraid and started to run. He had his own police record for sexual assault – though he had never been known to possess or use a weapon – and he feared getting into trouble again.

“I just kept running because I was scared, you know.” When he heard the sirens of police cars screeching towards the gas station he panicked and hid under a pick-up truck where, 40 minutes after the killing, he was arrested.

At the trial, DeLuna’s defence team told the jury that Carlos Hernandez, not DeLuna, was the murderer. But the prosecutors ridiculed that suggestion. They told the jury that police had looked for a “Carlos Hernandez” after his name had been passed to them by DeLuna’s lawyers, without success. They had concluded that Hernandez was a fabrication, a “phantom” who simply did not exist. The chief prosecutor said in summing up that Hernandez was a “figment of DeLuna’s imagination”.

Four years after DeLuna was executed, Liebman decided to look into the DeLuna case as part of a project he was undertaking into the fallibility of the death penalty. He asked a private investigator to spend one day – just one day – looking for signs of the elusive Carlos Hernandez.

By the end of that single day the investigator had uncovered evidence that had eluded scores of Texan police officers, prosecutors, defense lawyers and judges over the six years between DeLuna’s arrest and execution. Carlos Hernandez did indeed exist.

Liebman’s investigator tracked down within a few hours a woman who was related to both the Carloses. She supplied Hernandez’s date of birth, which in turn allowed the unlocking of Hernandez’s criminal past as the case rapidly unravelled.

With the help of his students, Liebman began to piece together a profile of Hernandez. He was an alcoholic with a history of violence, who was always in the company of his trusted companion: a lock-blade buck knife.

Over the years he was arrested 39 times, 13 of them for carrying a knife, and spent his entire adult life on parole. Yet he was almost never put in prison for his crimes – a disparity that Liebman believes was because he was used as a police informant. “Its hard to understand what happened without that piece of the puzzle,” Liebman says.

Several of the crimes that Hernandez committed involved hold-ups of Corpus Christi gas stations. Just a few days before the Shamrock murder he was found cowering outside a nearby 7-Eleven wielding a knife – a detail never disclosed to DeLuna’s defence.

He also had a history of violence towards women. He was twice arrested on suspicion of the 1979 murder of a woman called Dahlia Sauceda, who was stabbed and then had an “X” carved into her back. The first arrest was made four years before DeLuna’s trial and the second while DeLuna was on death row, yet the connection between this Hernandez and the “phantom” presented to DeLuna’s jury was never made.

In October 1989, just two months before DeLuna was executed, Hernandez was setenced to 10 years’ imprisonment for attempting to kill with a knife another woman called Dina Ybanez. Even then, no one thought to alert the courts or Texas state as it prepared to put DeLuna to death.

Hernandez himself frequently told people that he was a knife murderer. He made numerous confessions to having killed Wanda Lopez, the crime for which DeLuna was executed, joking with friends and relatives that his “tocayo” had taken the fall. His admissions were so widely broadcast that even Corpus Christi police detectives came to hear about them within weeks of the incident at the Shamrock gas station.

Yet this was the same Carlos Hernandez who prosecutors told the jury did not exist. This was the figment of Carlos DeLuna’s imagination

Many other glaring discrepancies also stand out in the DeLuna case. He was put on death row largely on the eyewitness testimony of one man, Kevan Baker, who had seen the fight inside the Shamrock and watched the attacker flee the scene.

Yet when Baker was interviewed 20 years later, he said that he hadn’t been that sure about the identification as he had trouble telling one Hispanic person apart from another.

Then there was the crime-scene investigation. Detectives failed to carry out or bungled basic forensic procedures that might have revealed information about the killer. No blood samples were collected and tested for the culprit’s blood type.

Fingerprinting was so badly handled that no useable fingerprints were taken. None of the items found on the floor of the Shamrock – a cigarette stub, chewing gum, a button, comb and beer cans – were forensically examined for saliva or blood.

There was no scraping of the victim’s fingernails for traces of the attacker’s skin. When Liebman and his students studied digitally enhanced copies of crime scene photographs, they were amazed to find the footprint from a man’s shoe imprinted in a pool of Lopez’s blood on the floor – yet no effort was made to measure it.

“There it was,” says Liebman. “The murderer had left his calling card at the scene, but it was never used.”

Even the murder weapon, the knife, was not properly examined, though it was covered in blood and flesh.

Other photographs show Lopez’s blood splattered up to three feet high on the walls of the Shamrock counter. Yet when DeLuna’s clothes and shoes were tested for traces of blood, not a single microscopic drop was found. The prosecution said it must have been washed away by the rain.

There appeared to have been an unseemly scramble to wrap up the crime scene. Less than two hours after the murder happened, the police chief in charge of the homicide investigation ordered all detectives to quit the Shamrock and allowed its owner to wash it down, sweeping away vital evidence that could have saved a man’s life.

The exceptionally lax treatment of evidence continued even beyond the grave. When Liebman asked to see all the stored evidence in the case, so that he could subject it to the DNA testing that was not available to investigators in 1983, he was told that it had all disappeared.

Having lived and breathed this case for so many years, Liebman says the most shocking thing about it was its ordinariness. “This wasn’t the trial of OJ Simpson. It was an obscure case, the kind that could involve anybody. Maybe those are the cases where miscarriages of justice happen, the routine everyday cases where nobody thinks enough about the victim, let alone the defendant.”

The groundbreaking work that the Columbia law school has done comes at an important juncture for the death penalty in America. Connecticut last month became the fifth state in as many years to repeal the ultimate punishment and support for abolition is gathering steam.

In that context, Liebman hopes his exhaustive work will encourage Americans to think more deeply about what is done in their name. All the evidence the Columbia team has gathered on the DeLuna case has been placed on the internet with open public access.

“We’ve provided as complete a set of information as we can about a pretty average case, to let the public make its own judgment. I believe they will make the judgment that in this kind of case there’s just too much risk.”

As for the tocayos Carloses, Carlos Hernandez died of natural causes in a Texas prison in May 1999, having been jailed for assaulting a neighbour with a 9in knife.

Carlos DeLuna commented on his own ending in a television interview a couple of years before his execution. “Maybe one day the truth will come out,” he said from behind reinforced glass. “I’m hoping it will. If I end up getting executed for this, I don’t think it’s right.”