Donald Reese was executed by the State of Missouri for a quadruple murder

According to court documents Donald Reese would go to an outdoor shooting range and would open fire killing James Watson, 54, and Christopher Griffith, 38; John Burford, 57, and his brother-in-law, Donald Vanderlinden, 64.

Donald Resse would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death

Donald Reese would be executed by lethal injection on August 13 1997

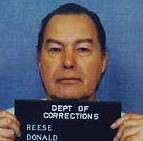

Donald Reese Photos

Donald Reese Case

It’s a few minutes past 5 a.m. when Donald Edward Reese pulls back the covers and sits up on the hard prison cot.

He grouses that the fluorescent lights burning overhead are keeping him awake. The truth is, the lights are only a minor distraction.

In about 19 hours, the state of Missouri plans to execute Reese. For nine years, three months and two days, he has lived on death row. Barring a compassionate act of God or government, today will be his last

Through the years, he has insisted that he is innocent of the crime that brought him to this moment–the murders of four men at a rifle range in central Missouri. He has appealed, and appealed again, but one after another the doors slammed shut on his case.

Now it is the last day, and he is running out of doors. Unlike the victims, who had no clue that death was approaching, Reese knows that chances are good he will never see another sunrise.

“I just never thought it would come this far,” he says

You can see the changes in Donald Reese.

When he arrived on death row, his combed-back hair was jet-black; now, it is weaved with gray. He once packed a trim 170 pounds on his 5-foot-10 frame, but after years of forgoing breaks in the exercise yard to work on his case in the legal library, he has put on 47 pounds.

Family and friends still call him “Ed,” but to officials at Potosi Correctional Center, he’s CP-65. The CP stands for “capital punishment.”

There have been times, through the years, when he thought the gray walls of prison would swallow him. He has leaned hard on his Bible, enrolling in a Bible correspondence course in the hope he might one day become a minister.

He also has passed the hours by writing songs–many involve a man who is jilted by the woman he loves. Dreams also are a common theme, with Reese drawing from the diary he uses to record the visions that come to him in the night.

He’s proud that he’s written 476 songs–a record, he thinks.

Reese also busies himself by learning embroidery. He draws his own designs, mostly religious symbols, and unravels his socks for thread. It’s not something he ever thought he would learn to do, but then he never thought he’d be on death row.

His journey to this day began Sept. 9, 1986. Reese dressed, drank a cup of coffee and drove the mile or so to his job at Hall and Riley Quarries in Marshall, Mo.

A loading machine broke down about two hours into his shift. Reese, a driver, was told to go home, but he had little reason to go there. His wife of 13 years had recently confessed she wanted to date other men. She took his boys, ages 10 and 12, most of the furniture and moved out.

Reese decided to go to the Marshall Junction Wildlife Area on the outskirts of town to shoot targets with his .30-caliber carbine rifle. Two other men–strangers–were there.

Reese lit a Marlboro from the cigarette box he kept in his shirt pocket. And this is where the story blurs.

Reese says it was as if he was caught in a bad dream–a nightmare in which a third man gunned down the first two, and then two other men who arrived in a car.

“I don’t care what nobody says, I didn’t kill them people,” he says firmly. He confessed under duress, he says; yes, he led police to the victims’ wallets and $1,200 in an old tin can, buried by the Salt Fork River, but he can explain.

“When I got back to my car, they were on the front seat.” The goods were planted there, he says–a ploy by the real killer to frame him.

The jury didn’t buy it. He was convicted of first-degree murder in the deaths of state conservation workers James Watson, 54, and Christopher Griffith, 38; he was never tried for the murders of John Burford, 57, and his brother-in-law, Donald Vanderlinden, 64.

The panel recommended that Reese be executed for both killings.

Griffith’s family, Quakers opposed to the death penalty, lobbied for life in prison without parole. The judge granted their wish–but sentenced Reese to death for Watson’s murder.

It’s almost 10 a.m.

Reese is perched in a holding cell 10 feet from where three lethal drugs are to be injected into his arm at 12:01 a.m.

An appeal filed on his behalf by another death row inmate is still pending before the U.S. Supreme Court. It seeks an emergency stay, contending there is new evidence in the case.

His court-appointed attorneys say there is nothing new. They are pinning their hopes on a request for clemency from Gov. Mel Carnahan.

Reese is still arguing his case: The shell casings found at the murder scene don’t match his gun. The prosecution argued his motive was robbery, but he had plenty of money–he’d just been paid. His gun could not fire fast enough to kill the four.

It still nags at Reese that he took his attorney’s advice and didn’t testify at his trial.

“I don’t even know how many hours I’ve spent working on this,” he says. “Too many to count. Don’t look like it’s going to do me much good, though.”

Reese never refers to the dead by name. It’s always “the victims” or “those men.” Though he prefers to think about his own situation, he does allow that the victims’ families are suffering.

“Oh, I know they’re hurting too, just like my family will be doing when they carry this out,” he says.

Reese misses being with the other inmates. He’s been in solitary confinement in the 12-by-14-foot holding cell for two days. He complains that every time the guards change shifts, he must undergo a “shakedown”–he is strip-searched and his cell is combed for contraband.

“I don’t know how they think I’m going to get anything in here. They don’t take their eyes off me,” he says.

There’s a TV, a cassette player and a few video games in the cell, but he can’t concentrate. He’s expecting his family to arrive at any time.

He dreads having to discuss what they should do if he’s executed. There’s no money for a burial. He had earned $10 a month cleaning prison showers, but that went for tobacco, peanut butter wafer bars, Doritos, paper and stamps. The Rev. Larry Rice of the New Life Evangelistic Center in St. Louis has promised to pay the $600 to have Reese cremated.

He’s turned in a list of people he wants to witness his execution: his son, Shawn, along with Shawn’s wife and her father; a woman who has become his pen pal; and Rice, who has befriended many of the men on the row.

Reese also has made out a will but refuses to divulge its contents.

“I don’t have much–mostly my songs, my artwork and my Bible,” he says.

It’s midafternoon when Reese gets word that the U.S. Supreme Court won’t grant him another hearing. He’s depressed, but refuses to let it show. He reminds himself that the governor has yet to rule.

His family is taking turns coming to talk to him. Reese longs to hold them one last time, but rules forbid any contact. Visitors must remain seated in plastic chairs behind a red line, three feet back from Reese’s cell.

They talk through the grated metal that separates them. They reminisce about the good times. Reese tells them he is sorry for the hurt he has caused them. He asks them not to cry. Reese wants to cry too, but he has to be strong for them.

“If it wasn’t for my family, it wouldn’t bother me,” he says. “I know I’m going to heaven.”

Reese was 12 when his own father was sentenced to two years for burglary. Reese vowed he’d never do that to his kids.

He’s disappointed in himself. There’s so much that he doesn’t know about his boys. His oldest, Todd, was 13 when Reese went to prison. Shawn was barely 12.

Donald Reese regrets not making an effort to keep in touch with them. When he met them again, they were 18 and 19.

Donald Reese wishes he had it all to do over again. He’d find a way to keep his family together.

He’d never own a gun.

It’s after 6 p.m. His family is not permitted back inside the prison until the execution.

His last meal is delivered. There’s no table in his cell, so he balances the disposable plate with six butterfly-fried shrimp, toast and french fries on his lap as he sits on his cot. He sips on his Coke, but decides to save his butter brickle ice cream for later.

“I wasn’t going to eat any of it,” he says. “It doesn’t seem right to eat from the hand that wants to kill you.”

The reality of his execution is starting to sink in. He is given a mild sedative that relaxes him but leaves him somewhat groggy.

“I never thought much about the death penalty before this happened,” he says. “I don’t support it. Christ don’t believe in killing.”

He’s glad when Rice, the minister, walks in about 7 p.m. Rice waits patiently as Reese talks on the telephone to his son, Todd.

Todd is angry that his state is preparing to kill his father. Reese tries to be strong for him. He tells his son that he shouldn’t be bitter.

Tears drip down Donald Reese’s face as he hangs up.

“It really hurts me to see them hurting,” he says.

Rice opens his Bible to Romans 8:38 and reads aloud: “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor present things, nor future things, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Donald Reese is beginning to calm. But the cycle of agitation begins again each time he makes a telephone call to a relative or friend.

There also are calls from reporters. What will you do, one asks, when you are taken to the execution chamber?

“I’m going to laugh at them,” Reese responds. “The Lord will punish them in his own way, whoever pushes the button.”

Rice says to Donald Reese: “Donald, tell me if I’m right or wrong. Prosecutors go way over there and make you look like the most evil person in the world. And the lawyers go way over here and try to make you look like you’re the next thing to a saint. The truth lies somewhere in between, doesn’t it?”

“Yes,” Donald Reese replies, then changes the subject.

The clock creeps toward 9 p.m. Still no word from the governor.

“If any case gets relief, this one ought to,” he says optimistically.

His thoughts are scattered. He wanders back to the summer of 1955. He is growing up on the Grand River, near Brunswick in central Missouri.

Donald Reese can’t resist rowing their small boat out into the river, and he falls into the murky water. He reaches for the boat, but the current carries it away. His brother, Gerald, on the shore, calls up to the house for help, but no one comes.

Gerald jumps into the water, grabs the boat and rows toward his younger brother. With all his strength, Gerald pulls Donald to safety.

Gerald also is there several weeks later when Reese slips into the river while trying to retrieve his toy sailboat. Reese splashes wildly but is unable to stay afloat. He feels himself sinking. Refusing to give up, he reaches up one more time. Gerald grabs his hand and pulls him to shore.

Forty-two years later, Donald Reese snaps out of his reverie. “Guess no one can save me this time,” he says, his voice trailing off.

At 10:30 p.m., a guard announces that Reese has a phone call. It’s his attorney; the governor has refused clemency. Rice is gone. A prison psychologist tries to comfort the condemned man.

Time seems to pick up speed.

Donald Reese’s hands and legs are shackled about 11:30 p.m. for the walk to the execution chamber–an 11-by-14-foot, hospital-white room with a gurney and a sink.

There, he’s told to lie on the gurney while a prison official tightens the leather straps across his heaving chest, arms and thighs. An IV is put in his arm. A heart monitor is attached to his chest. The lines are threaded through a hole in the wall to a room where the executioner stands by. A white sheet with tight hospital corners is pulled up to his neck.

At 11:55 p.m., the prison superintendent arrives. He reads the execution warrant and asks if Reese has any last words.

Donald Reese’s reply: “I love everybody.”

Then he is left alone in the room.

Minutes later, the white mini-blinds open, allowing his family, as well as witnesses for the state, to look in. No one is there to represent the victims.

Donald Reese turns his head to his right and looks at his son, Shawn.

A prison official announces that the first chemical–sodium Pentothal, which will render him unconscious–is being administered through the IV. Reese blinks rapidly as it begins flowing into his vein. His chest rises four times. He coughs. He breathes deeply and coughs again. After 45 seconds, he no longer moves.

His family stares blankly as he drifts away.

Word comes one minute later that the second drug–panchromium bromide, which stops his breathing–is being administered. And then the final drug–potassium chloride, which stops his heart.

A doctor watches in a neighboring room as the heart monitor flat-lines. At 12:05 a.m. on Aug. 13, 1997, Donald Reese is pronounced dead.

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-oct-05-mn-39476-story.html