Flint Hunt was executed by the State of Maryland for the murder of Baltimore police officer Vincent Adolfo

According to court documents Flint Hunt would jump out of a stolen vehicle and started to run. He was followed by Officer Vincent Adolfo. The pair ended up in a back alley where Hunt would shoot the Officer twice causing his death

Flint Hunt would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death

Flint Hunt would be executed by lethal injection on July 2 1997

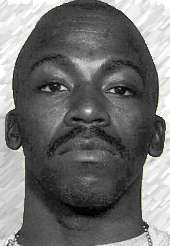

Flint Hunt Photos

Flint Hunt Case

Convicted cop killer Flint Gregory Hunt was executed early today by chemical injection at the Maryland Penitentiary, only the second prisoner put to death in Maryland in 36 years.

Hunt died about six minutes after an execution team began pumping heavy doses of the anesthetic sodium pentothal into his body, rendering him unconscious. Then followed two lethal chemicals, Pavulon, paralyzing his muscles, and potassium chloride, interrupting his body’s electrical impulses and stopping his heart at 12:25 a.m.

Stretched face up and strapped on a padded steel table, Hunt appeared calm, and his eyes were closed as the curtain over the witness window opened. He barely moved during the time the chemicals began flowing. After the final drug was administered, he appeared to take three quick breaths and was dead

Prison officials said that in his final statement, Hunt, who converted to Islam on death row, asked for forgiveness and said a prayer in Arabic.

Hunt was convicted of first-degree murder in the 1985 killing of Baltimore police officer Vincent J. Adolfo. He was shot twice, once in the back, as he tried to arrest Hunt on an auto theft charge.

Hunt, who turned 38 Friday, had fought his execution in a string of futile court battles. During his nearly 10-year stay on death row, he repeatedly expressed remorse for the killing.

Hunt’s execution followed an unsuccessful series of last-minute legal maneuvers by defense attorneys in state and federal courts and in Maryland Gov. Parris N. Glendening’s office. The Supreme Court rejected an emergency request for a stay just hours before the execution.

But Hunt found some comfort in two accomplishments in his final days. He was allowed to switch the method of his death to injection from asphyxiation in the state’s gas chamber, a method he had originally requested

Hunt also was allowed to marry a 34-year-old Annapolis woman he had met during a year-long telephone courtship from death row. The two were wed Saturday in a 15-minute Islamic ceremony attended by family members and prison guards at the Maryland Correctional Adjustment Center, or “Supermax,” a maximum security fortress adjacent to the penitentiary where death row inmates are housed.

In a gruesome attempt at irony, Flint Hunt said recently he wanted to be executed in the gas chamber — where the condemned man gasps convulsively and sometimes slams his head against the death chair — to maximize the violence of his death at the hands of the state. In a jail-house interview with the Baltimore Sun, he said he had opted for gas over the less dramatic injection method because it would look more like “murder.”

But late last week, Flint Hunt, through his attorneys, successfully petitioned the Maryland Court of Appeals to allow him to switch to injection. The attorneys said Hunt’s mother and bride wanted to witness the execution, and Hunt opposed them seeing him die by gas. The family members ultimately did not attend the execution. They were barred, prison officials said, because the group of 12 volunteer witnesses, the maximum allowed under state law, had already been selected

Some state officials questioned Hunt’s motivation for both the marriage and the switch in execution method, saying they could be construed as delaying tactics to buy him a few more weeks of life. A strenuous state resistance to either request could have triggered protracted litigation, necessitating a stay of the execution.

Prison officials fought the switch in execution method only briefly and accepted a Court of Appeals order permitting the change. The marriage, like the 100 to 200 permitted annually in the state’s 22,000-prisoner population, was allowed with few delays, and no litigation ensued.

Flint Hunt’s switch to injection “was a genuine change of heart,” attorney Fred Warren Bennett said in an interview this week. “And the marriage has nothing to do with” delaying tactics.

Flint Hunt had been the last prisoner in Maryland scheduled to die in the little-used, 42-year-old gas chamber. Only four prisoners have been executed in the chamber since 1957, the last in 1961

With the state’s conversion three years ago to chemical injection, Hunt was the only death row inmate to indicate a preference for gas during a 60-day period in 1994 when prisoners were given that option. The gas chamber will now be shut, and all 16 remaining death row inmates face injection.

Many states in recent years have converted to chemical injection, saying it is more humane than traditional methods, such as the gas chamber, electric chair, firing squad or hanging. Death penalty opponents contend that the chemical injection method is calculated merely to make executions more palatable to the public.

Flint Hunt was the first prisoner executed in Maryland since triple killer John F. Thanos died by injection May 17, 1994. Before Thanos, there had not been an execution since Nathaniel Lipscomb, a murderer and rapist, died in the gas chamber June 9, 1961

Flint Hunt learned the day he was to die on Friday. But the exact time and date of Hunt’s execution was kept secret from the public — the result of an old law designed to prevent large crowds from gathering at the penitentiary.

Nonetheless, nearly 250 demonstrators protesting the death penalty lined the sidewalk across East Madison Street from the penitentiary. Some had been there since Sunday.

As the wax from their candles puddled on the walkway, the crowd, which included children and teenagers, chanted, sang and handed out anti-capital-punishment pamphlets.

Behind the various political, religious and amnesty groups, Hunt’s sister, Frances Hunt, sat on a folding chair and clung to her friends. In her hand was a picture of her brother.

“All this support is just beautiful,” she said through tears. “I just can’t even explain what I’m feeling right now, because I don’t even know

Two blocks down, at the stroke of midnight, about 100 friends and relatives of Adolfo sang “Hey, Hey Goodbye” and cheered.

“If the protesters at the other end went through what we went through, they’d feel differently about this whole thing,” said the dead officer’s sister-in-law, who would not give her name.

Critics say the death penalty has been applied disproportionately against black prisoners. Of the two executed in Maryland in recent years, Thanos was white, and Hunt was black. Thirteen of the 16 prisoners on death row are black.

Since executions were centralized at the penitentiary in 1922 (rather than carried out in the state’s 23 counties and Baltimore), 82 prisoners have been put to death, 63 of them black. All were men. Before 1955, executions were by hanging.

Flint Hunt was convicted in 1986 of fatally shooting Adolfo during a struggle in an alley on Nov. 18, 1985, as Adolfo was trying to arrest Hunt

According to prosecutors, Flint Hunt drew a .357 magnum pistol and shot Adolfo once in the chest, then fired a second time, hitting him in the back as the officer staggered away.

It was the second shot that caused prosecutors to charge Flint Hunt with first-degree murder and enabled them to demand the death penalty.

At his trial, police and prosecutors characterized Hunt as a cool and calculating street hustler who shot Adolfo in cold blood.

Flint Hunt admitted the shooting, but defense attorneys and family members described him as a confused and drug-obsessed youth who panicked and fired at Adolfo in the emotion of the moment as he was being chased and arrested. The shooting lacked the premeditated intent, they said, to justify the death penalty.

“He did not intend to kill” Adolfo, defense attorney Judith Catterton told a reporter after a court hearing for Hunt last summer. “. . . This was a killing in a panic state.”

Flint Hunt pursued numerous appeals in state and federal courts but was unsuccessful at every turn.

In the last hours of his life, Hunt was kept in a holding cell adjacent to the execution room in the hospital wing of the penitentiary. There, under the eye of a six-member death watch team.

He was visited by family members, met with his attorneys, listened to music and watched a video, “Braveheart.” He also prayed with a prison chaplain who is a Muslim imam.

Officials set up three telephone lines in the death house in case a last-minute stay of the execution was ordered. A short time before his death, Hunt was escorted by guards from the holding cell to the bare execution chamber and strapped face-up to a padded steel table, his arms extended almost straight out from his body, fully visible to the 12 witnesses, including six reporters, who were authorized to be present. An intravenous line was inserted into each arm, one to feed the deadly chemicals into Hunt’s body, the other as a backup. The lines led to a partition a few feet away behind which members of a second team — a specially trained execution squad headed by William W. Sondervan, the prison system’s security chief — checked to see that the chemicals were loaded properly and in the correct sequence in their syringes. At a signal from Sondervan, team members, watching through a one-way window, released the chemicals.

Among those who witnessed the death were Adolfo’s widow, Karen. She left without making a comment. However, at a news conference later, local Fraternal Order of Police leader Gary McLhinney read a statement on Karen Adolfo’s behalf.

“The events of today are not about vengeance, but about justice,” the statement said. “Closure can occur today for the Adolfo family and the police officers of Baltimore City