Judy Buenoano is a female serial killer who would be executed in Florida for two murders but is believed to be responsible for many more.

Judy Buenoano would marry her first husband James Goodyear who would pass away in a case doctors thought were natural causes

Judy Buenoano would have a relationship with Bobby Morris who would die in his sleep five years later

Judy Buenoano son would become disabled because of an illness and would later drown

Judy Buenoano would begin another relationship with John Gentry who would be severely injured when his car exploded

When police began to investigate the car bombing they took a closer look at Judy Buenano and the amount of death that followed her. Turns out before the car bombing Judy had been giving John Gentry vitamins that were laced with arsenic

Investigators would exhume the bodies of her first husband, her son and Bobby Morris all of which had traces of arsenic in their systems

Judy Buenoano would be arrested, convicted in the murder of James Goodyear in which she was sentenced to death. Judy would receive a life sentence for the murder of her son and 15 years in prison for the attempted murder of John Gentry

Judy Buenoano would be executed by way of the electric chair on March 30 1998

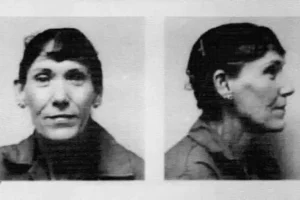

Judy Buenoano Photos

Judy Buenoano FAQ

When was Judy Buenoano executed

Judy Buenoano was executed on March 30 1998

How was Judy Buenoano executed

Judy Buenoano was executed by way of the electric chair

Judy Buenoano Execution

Gone were the painted, manicured fingernails and the fashionable dark hair. Gone was the tough-edged woman who drove around Pensacola in a Corvette and told bigger-than-life stories about her life, her businesses and her Chanel perfume.

Judy Buenoano walked shakily to Florida’s electric chair Monday, her head freshly shaved. Guards had covered it with gel – highlighting every bump, every vein – to conduct the electricity better. She wasn’t the same person who had boasted that Florida would never execute her. She was, simply, an old, frightened woman.

And by 7:13 a.m., Judy Buenoano, 54, had become the first woman executed in the state in 150 years and the first woman to die in the chair.

Prosecutors called Buenoano the “Black Widow,” saying she attracted men to kill them for insurance money. She was executed for killing her Vietnam veteran husband with arsenic in Orlando 27 years ago, but Pensacola juries also found her guilty of drowning her paralyzed son in 1980 and trying to firebomb her boyfriend in 1983.

She had gotten about $240,000 in insurance money from the deaths of her husband, son and a common-law husband who died of arsenic poisoning in Colorado in 1978. Prosecutors said she had used some of the money for a new car, for a diamond ring, to start her nail salon, to live the high life.

She might have gotten away with her crimes, they said, if she hadn’t botched the bombing and left a trail back to her.

Florida had not executed a woman since 1848, when a freed slave was hanged for killing her former master. Because of that, Buenoano’s death attracted widespread media attention. Early Monday, lights from TV cameras and satellite trucks rivaled those beaming from Florida State Prison. Reporters outnumbered protesters.

Judy Buenoano met with her two children, a cousin and her spiritual adviser through the night. They had Communion and a final contact visit. Buenoano dozed from 1 until 4 a.m., when she received a last meal of steamed vegetables, fresh strawberries and hot tea.

Throughout Sunday, she had been talkative and upbeat, a corrections spokesman said.

But when she entered the death chamber shortly after 7 a.m., Buenoano held tightly to the hands of two male guards who helped her walk. She was pale and terrified. But she seemed determined to face her death with a kind of stoic dignity.

As authorities strapped her in, she grimaced, especially as they tightened the belt around her chest. Through most of the preparations, she kept her eyes shut, not looking at the people who gathered to watch, including her spiritual adviser and the brother-in-law of Air Force Sgt. James Goodyear, her poisoned husband.

Asked whether she had a last statement, Judy Buenoano said in a barely audible voice, “No, sir.” Moments later, as the current flowed, her fists clenched. She seemed almost dwarfed in the 75-year-old oak chair. Smoke rose from the electrode attached to her right leg.

The witnesses watched silently. In the front row sat Orange-Osceola Chief Judge Belvin Perry, who prosecuted Buenoano in 1984. Next to him was Dusty Rhodes, who as a state attorney investigator had gathered evidence against Buenoano in the Goodyear case.

The two had become experts on arsenic. They had watched the exhumation of Goodyear’s body to check for poison. They had tracked down a witness who said Buenoano told her not to divorce her husband but instead kill him with arsenic. But you’ll need the stomach for it, the friend quoted Buenoano as telling her.

Perry and Rhodes called Judy Buenoano a cold, calculating killer.

“It was very serene, clinical,” Perry said of the execution. “It brings finality and a final chapter in this saga.”

As they drove home from Starke on Monday, the two talked about how Buenoano’s death had been humane compared with the agony Goodyear endured and the pain her 19-year-old son, Michael, felt as he drowned in a river with braces on his arms and legs.

But family members described a different Judy Buenoano. They called her a devoted Roman Catholic, a beloved mother and grandmother, a woman who had had a tough childhood but went on to raise a family of her own. They said the case against her was circumstantial and called prosecutors overzealous and high courts cowardly for not setting aside her death sentence.

Sunday, before they entered the prison to say goodbye to their mother, Buenoano’s daughter, Kimberly Hawkins, and son, James Buenoano, stood before cameras and asked the state not to commit a “hate crime against God and humanity.”

The pleas did not work. The courts refused a last-minute stay.

Twelve civilian and 12 media witnesses, plus corrections officials, were stuffed into a tiny room separated by glass from the death chamber. Female guards were brought in to be with Buenoano in her final days. One of them walked into the chamber with Buenoano, but male guards handled the execution.

Outside, death-penalty opponents and supporters waited for word on the execution – the third in Florida in eight days.

Members of Pax Christi, a state group organized with the Roman Catholic Church, held signs that read Buenoano is “a woman not a spider.”

“Executions are just an excuse for vengeance toward people,” said Martina Linnenahm, a member of the group.

Death-penalty supporters included Larin Cone, whose brother, Floyd Jr., was killed in 1981 when Edward Kennedy escaped from prison and shot him and a state trooper to death. Kennedy was executed in 1992.

Cone said Judy Buenoano did not deserve mercy because of her gender. “She killed just like a man,” Cone said, “so she should receive the same treatment as a man.”

Wayne Manning of Lawtey had a day off from work, so he brought his 7-year-old grandson, Steven, to the prison.

“He needs to learn what is going on in this world,” Manning said. “Maybe he won’t get into a situation like this, himself, if he is exposed to it now.”

https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/os-xpm-1998-03-31-9803310252-story.html