Leo Jenkins was executed by the State of Texas for a double murder

According to court documents Leo Jenkins would rob a pawn shop and in the process would shoot and kill a sister and brother who were working: Mark Kelley and Kara Kelley Voss

Leo Jenkins would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death

Leo Jenkins would be executed by lethal injection on February 9 1996

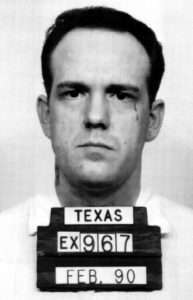

Leo Jenkins Photos

Leo Jenkins Case

Linda Kelley awakened Friday morning with a grim hope — that she might watch the killer of her children die by suppertime.

Nothing has seemed right, or quite real, to Kelley and her family since that afternoon in August 1988 when Leo Jenkins sauntered into the Golden Nuggett pawnshop in Houston, leveled a .22-caliber pistol at the two young people working there, and ended the lives of Kara Kelley Voss, a newlywed who was just 20, and Mark Kelley, 26, whose second child was four weeks old.

In that flash of unthinking violence, everything Linda Kelley had ever known or believed in was shattered, replaced with a deep, howling pain that will never go away.

But at 6:22 p.m. Friday, Kelley watched with a steady gaze, anger and hate still pounding in her heart, as a lethal dose was pumped into Jenkins’s veins. Surrounded by her husband, her remaining daughter, her daughter-in-law, and her husband’s 90-year-old mother, Kelley stared coldly at the gurney where Jenkins lay, thinking of everything he had ruined, everything she had lost. It was so easy, she said afterward, to look on as he died

“I’m sorry,” she said, “but this was not difficult at all. I’m glad it’s over and I’m glad it’s done, and I’m glad he’s off this earth. . . . I have peace at heart.”

The Kelleys were the first family in Texas to be permitted to watch the execution of the murderer of their loved ones, but their experience reflects a growing trend in the arena of victims’ rights and, death-penalty opponents fear, a disturbing focus on up-close vengeance.

In the past few years, seven of the 38 states that allow the death penalty, including Virginia, have agreed to permit victims’ families to witness the state’s final action on their behalf. Other states also are considering policy changes, propelled by advocates who argue the families of murder victims have as much right to be present at the last moment as the friends and relatives of the dying inmate

EXECUTION IN TEXAS: A SATISFYING END FOR FAMILY OF TWO VICTIMS

By Sue Anne Pressley

February 11, 1996

Linda Kelley awakened Friday morning with a grim hope — that she might watch the killer of her children die by suppertime.

Nothing has seemed right, or quite real, to Kelley and her family since that afternoon in August 1988 when Leo Jenkins sauntered into the Golden Nuggett pawnshop in Houston, leveled a .22-caliber pistol at the two young people working there, and ended the lives of Kara Kelley Voss, a newlywed who was just 20, and Mark Kelley, 26, whose second child was four weeks old.

In that flash of unthinking violence, everything Linda Kelley had ever known or believed in was shattered, replaced with a deep, howling pain that will never go away.

But at 6:22 p.m. Friday, Kelley watched with a steady gaze, anger and hate still pounding in her heart, as a lethal dose was pumped into Jenkins’s veins. Surrounded by her husband, her remaining daughter, her daughter-in-law, and her husband’s 90-year-old mother, Kelley stared coldly at the gurney where Jenkins lay, thinking of everything he had ruined, everything she had lost. It was so easy, she said afterward, to look on as he died.

“I’m sorry,” she said, “but this was not difficult at all. I’m glad it’s over and I’m glad it’s done, and I’m glad he’s off this earth. . . . I have peace at heart.”

The Kelleys were the first family in Texas to be permitted to watch the execution of the murderer of their loved ones, but their experience reflects a growing trend in the arena of victims’ rights and, death-penalty opponents fear, a disturbing focus on up-close vengeance.

In the past few years, seven of the 38 states that allow the death penalty, including Virginia, have agreed to permit victims’ families to witness the state’s final action on their behalf. Other states also are considering policy changes, propelled by advocates who argue the families of murder victims have as much right to be present at the last moment as the friends and relatives of the dying inmate.

“This is basically what the death penalty has come down to,” said Richard Dieter, director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington. “Having the death penalty as a deterrent has not seemed to work. There doesn’t seem to be the need to protect society to have the death penalty — prisons can do that. One of the remaining justifications is vengeance, almost like something for the family of the victim, or the victims themselves in a way.

“It’s sort of a symbolic gesture,” he said, “but what they will see is not so much something that gives them retribution, not anything like what they suffered. They won’t see a violent death. What they will see is another family in grief over their own son, or brother, or husband.”

But to Linda Kelley’s way of thinking, Dieter was wrong. What she saw, she said, was immensely satisfying, knowing Leo Jenkins would never enjoy a meal again, or watch a television program, or do any of the simple things her two children had been denied

A recent past leader of the Parents of Murdered Children group in Houston, she had testified before the state legislature to allow the change and, when that effort failed, worked to persuade the Texas Criminal Justice Board to broaden its policies — never realizing her family would be the first to exercise the option.

In that sense, Jenkins assisted her; by giving up his appeals, he chose to die years before his last execution date would have been set.

“I have to give the man credit — he made the decision not to drag it out any longer and I’m thankful he was willing to do this,” said Kelley, 55. “But I will never forgive him for what he did. Our life is over. We are not, and never will be, the same people. My husband and I are not living, we’re just existing. We don’t care whether we live or die.

By society’s measure, Leo Jenkins was a loser.

When he and an accomplice walked into the Kelley family pawnshop Aug. 29, 1988, intending to rob the business to feed a bad drug habit, he already had served time for burglary and theft, and had been released only a few months earlier from his latest round in prison. Three days after the Golden Nuggett murders, he was arrested, and confessed to the killings.

In time, on Texas’s death row, Jenkins followed the well-worn path to religious redemption and, in his last statement from his gurney on Friday, told onlookers that “I believe Jesus Christ is my Lord and Savior.” He also said he was sorry for “the loss of the Kelleys, but my death won’t bring them back. I believe that the state of Texas is making a mistake tonight. Tell my family I love them.” He paused, then said, “I’m ready.”

Jenkins’s sister, Deborah LeMaster, said he was troubled that the Kelley family was going to watch him die. He could not understand, she said, what it would accomplish.

“He said that he had done a very bad wrong, and that he could never make it right except by doing what he was doing,” said LeMaster, 43, in a telephone interview from her Dallison, W.Va., home. Because of childhood adoptions, she had located her brother for the first time only three years ago, shocked to find he was imprisoned on death row. They were never to meet in person.

“He thought, he hoped, that his death would be enough to satisfy the Kelleys, so they could go on with their lives,” she said. “But he thought it was low, that the warden would let them watch.”

But that was what kept the Kelleys going sometimes, knowing that someday Leo Ernest Jenkins Jr., 38 — a red-haired man with a strong physique and numerous tattoos, the source of their numbing grief — would be wheeled into the death chamber. And that perhaps they, too, would be there someday as he left the world

In the meantime, Linda Kelley has drifted through a haze of grief. She visits her children’s graves obsessively, talking to them, putting balloons out for their birthdays, tracing her fingers around the names engraved on their tombstones, and remembering how happy she was to be pregnant with them, long ago, cheerfully picking out the names with her husband.

“I keep thinking, My God, these are my babies. Oh, Mark. Oh, Kara. I’m supposed to die first.’ “

When it was over Friday, the Kelley family trooped stoically out of the building that holds the death chamber, arm-in-arm, dry-eyed, 90-year-old Angeline Kelley supported by Mark and Kara’s sister, Robin. They had been nervous before the execution — maybe he would back out at the last minute, maybe this would never happen.

Earlier in the week, they had toured the death room, and considered the sight of Jenkins on the stretcher beyond the glass wall and, now, something like relief shone on their faces

Linda Kelley had no sorrow for the murderer, she said. Even to the last, she thought his attitude was bad — arrogant, the way he said the state of Texas was wrong to kill him. She wanted to see more remorse, more feeling.

She thought he was allowed to die with much more dignity than her children, who were shot in the heads like animals. She said she would encourage every family in her position to witness an execution.

“It is a chapter closed for us,” she said Friday. “When we go home, we still have to deal with the fact that Mark and Kara aren’t here, but I’m going to go to the cemetery tomorrow and I’m going to tell Mark and Kara that he’s gone and I’m glad he paid the price for what he did. I’m glad I watched it. I’m glad I was allowed to watch it. I don’t have the weight that I had when I went in there. Because your imagination runs wild if you don’t see something for yourself. I wouldn’t have known what had happened. . . . And I will be able to go to sleep tonight.”

But Linda Kelley is too wise, too well-versed in the complexities of grief, to think her pain will ever go away.

Today she did visit Mark and Kara’s grave and tell them this horrible man was dead. And then, after she neatened up their flowers and patted their tombstones and cried once more as if it all happened yesterday, she turned to her husband, Jim, and together, they went home — still trying to figure out how to survive the rest of their lives.