Randy Haag was sentenced to death by the State of Pennsylvania for the murder of Richard Good

According to court documents Randy Haag would kidnap Richard Good who would be brought to a remote location where he would be fatally shot and thrown into the river

Randy Haag would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death

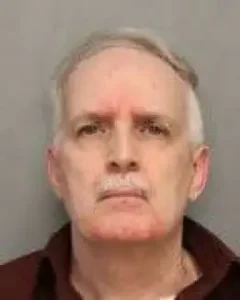

Randy Haag Photos

Randy Haag Now

Parole Number: 1209S

Age: 65

Date of Birth: 04/12/1958

Race/Ethnicity: WHITE

Height: 5′ 08″

Gender: MALE

Citizenship: USA

Complexion: LIGHT

Current Location: PHOENIX

Permanent Location: PHOENIX

Committing County: BERKS

Randy Haag Case

The incident from which the convictions arose took place in Berks County where appellant and several cohorts kidnapped and shot an individual, Richard Good, and then disposed of the body in a river. The evidence linking appellant to the crime consisted of, inter alia, the following.

One of Randy Haag’s acquaintances, Steven Grynastyl, testified that one evening in February or March of 1982 he received a phone call from a friend, Michael Slote, who informed him that appellant was “all cranked up” and wanted to kill Richard Good that night. Grynastyl went immediately to Slote’s residence, where he met with Slote, appellant, and another acquaintance, Howard Weisman. Appellant offered $5,000.00 for Slote and Grynastyl to kill Good immediately with a high-powered rifle, wrap the body in carpet, weight it down, and dump it in a lake or river. Appellant and Weisman then decided, however, that it would be too risky to go through with the killing that night, due to the fact that freshly fallen snow would leave traces *394 of footprints. Grynastyl also testified that, approximately one week previous to this, he heard appellant express a desire that Good be killed because Good owed appellant and Weisman money for cocaine purchases.

Months later, on July 14, 1982, Slote had a conversation with Good’s daughter, Vickie Lee Good. Miss Good testified that Slote asked her to have her father call him later that day because Slote expected to receive some cocaine. Around 10:00 p.m. that evening, Miss Good was dispatched by her father, who earned his living as a drug dealer, to a pay phone to call Slote and inquire whether the cocaine was available. Slote then told her to have her father come, alone, to see him after 11:00 p.m. Good departed at the appointed hour, in his black Corvette, and was never again seen alive by his daughter. Good planned to visit his girlfriend after stopping to see Slote, but never arrived at her house. Miss Good testified, also, that her father owed money to Slote and appellant for drugs, and that, a year earlier, her father and appellant had been involved in an altercation with one another.

An individual who resided in a townhouse with appellant and Weisman at the time of the crime, Van Scott Peters, who worked as a drug runner for Randy Haag, testified that he visited Slote’s house late in the evening of July 14, 1982. He was taken there by appellant, Weisman, and one Michael Sands. Upon arriving there, appellant instructed everyone to wait in Slote’s bedroom so that Good, who was expected to arrive soon, would not see them. Peters had previously heard appellant say that he disliked Good and that Good owed him money. When Good arrived, he was led into the bedroom by Slote, whereupon Sands pointed a rifle at him. Slote and Weisman grabbed Good, and appellant took the rifle from Sands and began beating Good with the rifle butt. Randy Haag then yelled at Good and punched him repeatedly, causing him to fall to the floor, after which appellant, Weisman, and Slote tied him up and carried him to the basement. Randy Haag then directed Peters and Sands to watch that Good did not untie himself. Less than an hour *395 later, around midnight, while Good was still alive, appellant gave Peters some money, cocaine, and the keys to Good’s black Corvette and told him to drive the car to Florida. Peters, accompanied by Sands, departed immediately and drove to Hollywood, Florida, where they stored the car

On July 20, 1982, police were alerted when Good’s body was discovered by a fisherman at the Susquehanna River. Good had been shot in the head, and his body was partially submerged, having been bound in rope, wrapped in carpet, and weighted down with concrete blocks and chains secured by a connecting link and padlock.

Peters testified that, upon his return to Berks County from Florida, appellant and Weisman told him that the Pennsylvania State Police wanted to talk to him and that he had been spotted in Florida in the black Corvette. They instructed Peters to tell the police that he had been driving in Florida until his car broke down and that a man in a black Corvette picked him up. Appellant chastised Weisman for not having attached sufficient weight to Good’s body to keep it submerged. Appellant also instructed Peters to remove a concrete block from outside their townhouse and to travel in appellant’s car to a garage that appellant used for storage, and to remove all of the carpet scraps from the garage. Weisman and Peters later dumped the block and the carpeting into a landfill dump site, for appellant had instructed them to dispose of the items. Weisman told appellant and Peters that a length of chain should be purchased and kept on hand, since police might become suspicious if they found out that Weisman purchased a chain at Leinbach Hardware Store just before Good’s death. The chain had been used to bind Good’s body for disposal. Hence, Peters and Weisman purchased a new chain at a different hardware store.

Peters testified further that, on July 14, 1982, when Good was attacked at the Slote residence, yet another individual, Bruce Ream, was present in the house. Ream did not participate in the criminal incident. He resided in Slote’s *396 house, and remained in another bedroom throughout most of the evening.

The testimony of Sands was also presented at trial. Sands substantiated in all major respects the account given by Peters as to the events which occurred at Slote’s residence on the evening of July 14, 1982. Sands had not, however, noticed the presence of Ream in Slote’s house that night.

Next, Ream testified that he resided in one of the bedrooms at Slote’s house, and that he had gone to bed around 9:30 p.m. on the evening in question. Slote had earlier said to him, “Tonight’s the night.” He remained in his bedroom with the door closed all evening and emerged only briefly on one occasion, at which time he saw appellant, Slote, Weisman, Peters, and Sands in another bedroom snorting cocaine. After returning to his bedroom, he heard a number of sounds through the thin walls. He heard a car arrive, and then heard Slote answer the door. Good’s voice was detected, and a number of people started yelling. Ream heard appellant say, “You’re going swimming.” He then heard something being dragged down the basement steps, and an argument ensued in the basement. Shortly thereafter, Ream heard a car being driven away from the house, and saw the car’s brake lights in the darkness. Approximately fifteen minutes later, he heard a single gunshot.

Ream heard nothing more that night and departed for work early in the morning. After returning home in the evening, on July 15, 1982, he overheard a meeting of appellant, Slote, and Weisman. They were saying, “Just keep your mouth shut. Keep a cool head.” Slote asked appellant for “double payment” for being the “trigger man,” and then Slote and appellant went to another room to discuss the matter. Appellant told Ream to keep his “mouth shut.”

Approximately two days later, Ream listened to another conversation between appellant and Slote. Randy Haag gave Slote two ounces of cocaine and said, “I’ll pay you the rest *397 later.” Many months later, while police were investigating Good’s death, appellant told Ream he would like to have the Pennsylvania State Police barracks blown up. Appellant also named four state police officers who were involved in the investigation of Good’s death, and said he would “like to have them found in the river, too.” In addition, appellant said it was Weisman’s fault that Good’s body had been discovered, and that he, i.e., appellant, was only supposed to have handled the “financial end.”

A cashier from the Leinbach Hardware Store testified that late in the summer of 1982 he was asked by Weisman to destroy a copy of a charge slip, dated July 13, 1982, which reflected Weisman’s purchase of rope, chain, a connecting link, and a padlock. The cashier did not, however, destroy the charge slip. The items purchased were just like those found wrapped around Good’s body when it was recovered from the river. Also, a former automobile dealer testified that he sold his dealership to appellant approximately one year prior to Good’s death, and that the dealership office had been carpeted in a tricolored carpet exactly like the one in which Good’s body was found.

Scientific evidence was adduced at trial, too, including the results of an autopsy performed on Good’s body on July 20, 1982 by a forensic pathologist, Dr. Mihalikis, who concluded that the cause of death was a shotgun blast to the head. Dr. Mihalikis stated that death likely occurred five days, plus or minus one day, prior to the autopsy. This would place the date of death between July 14 and July 16, 1982. Notably, Ream testified that Slote owned a shotgun around that time, but that he had not seen the gun after July 14, 1982. A police search of Slote’s bedroom uncovered two shotgun shells, loaded with no. 2 size lead pellets. The pellets recovered from Good’s skull during the autopsy were of size no. 2.

Evidence of the time of death was also furnished through the testimony of a forensic toxicologist who examined stomach contents removed during the autopsy. The contents included beef fibers, leafy vegetable matter, and processed *398 wheat grain. The toxicologist testified that these substances could have been the remains of prepared lunch meat, lettuce, and bread. He also gave his opinion that the food had been consumed three to six hours before death. This is significant because Miss Good testified that she fixed her father a sandwich of bologna, cheese, lettuce, and bread at 8:30 p.m. on July 14, 1982, just two and one-half hours prior to his departure to visit Slote.

Upon consideration of the foregoing evidence, we hold that appellant’s guilt was plainly established beyond a reasonable doubt. Appellant has characterized the Commonwealth’s evidence as contradictory and “all over the park.” Such a characterization is patently without basis. Our examination of the testimony, as heretofore recounted, discloses remarkable consistency in its content. The testimony of numerous witnesses, as well as the physical evidence introduced, all supported the jury’s determination that appellant participated in the kidnapping and murder of Good on July 14, 1982

https://law.justia.com/cases/pennsylvania/supreme-court/1989/522-pa-388-1.html