Robin Myers was sentenced to death by the State of Alabama for the murder of Ludie Mae Tucker

According to court documents Robin Myers would break into a home and stab two people: Ludie Mae Tucker and a guest. Ludie Mae Tucker would die from her injuries.

The case would go unsolved for nearly two years until Robin Myers would be arrested,

Robin Myers would be convicted and sentenced to death

Robin Myers has maintained he had nothing to do with the murder

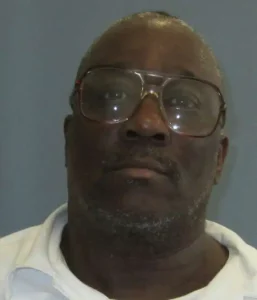

Robin Myers Photos

Robin Myers FAQ

Where Is Robin Myers Now

Robin Myers is incarcerated at Holman Prison

Robin Myers Case

There was the VCR, taken from the home and swapped hours later for crack cocaine. There were witnesses to that trade, but nearly all, at some point, changed their stories. No physical evidence identified who fatally stabbed Ludie Mae Tucker in her Decatur home in October of 1991.

No murder weapon.

No bloody clothes.

No hair samples.

Even the other victim, who survived her stab wounds, could not identify her attacker. Yet, according to one juror, 12 citizens in Decatur did what they thought they had to do: They convicted Robin “Rocky” Myers of killing his neighbor.

“They never ever placed him in the house that night,” said Mae Puckett, who served on the Morgan County jury in 1994.

At the time, it looked like holes in the case would trigger a hung jury, she recently told AL.com through tears. She said two or three jurors were dead set on guilty. But if the case ended in a mistrial, it could go back to court. Puckett said she and other jurors feared Myers would be executed. ”Those of us who thought he was innocent had very strong feelings about it.. (but) we knew those guys weren’t going to change their mind,” she said. “We decided to vote him guilty… the best thing we thought we could do was spare his life.”

The jury voted to send Myers to prison for the rest of his life, without the possibility of parole.

“Then the judge just turned everything around.”

In a twist of Alabama law, the judge overruled the jury’s decision and sentenced Myers to death.

Myers, now 61, has been on Alabama’s Death Row for 29 years. His former lawyer missed a key deadline in 2003, ending his hopes of appeal. Now, his fate rests with Gov. Kay Ivey.

If put to death, he could become one of the first in the nation to be executed by nitrogen asphyxiation, a newly approved and untested method in Alabama.

His lawyer, Kacey Keeton, is working to seek clemency from the governor. The state hasn’t tested the new execution method yet, but Keeton said, “We are actively pushing his clemency case forward because that could happen at any time.”

Myers’ ex-wife Debbie Anthony, told AL.com she still believes he is innocent.

“I know he was easy to blame,” she said. “He wasn’t really smart, he was on drugs, he was Black. So why not?”

The crime

At 12:19 a.m. on Oct. 5, police received a 911 call from a woman living along a busy road, just across the railroad tracks from downtown Decatur. The dispatcher would later testify that all that the caller could do was breathe heavily into the phone.

The woman eventually gave police her address and was able to say she was “cut.” Officer James Tilley was close by, patrolling near a house known for selling crack. When Tilley walked inside the victim’s home a minute after the call, he found a woman bleeding from a stab wound to her side. He quickly realized there was a second, more seriously injured woman who had been stabbed three times in the stomach and once in the chest.

As paramedics rushed to the house, 69-year-old Ludie Mae Tucker drifted in and out of consciousness. She was able to tell police that her attacker was a short, stocky Black man, who was wearing a white or light-colored T-shirt with blood on it and possibly a plaid shirt overtop.

“She did not indicate that she knew the subject,” Tilley would later say in court.

While being loaded in the ambulance, Tucker was able to hold one officer’s hand. “Sugar, it hurts so bad,” she said, according to trial transcripts.

Tucker died at Decatur General Hospital.

Her cousin, Marie Dutton, survived the attack.

Dutton, later testifying about what happened that night, said she had been with her cousin all day. The women went to bed around 11 p.m, she said.

At some point around midnight, Dutton awoke to the doorbell.

She got up and saw Tucker standing at the front door with the blinds pulled back. Dutton said a man was talking about being hurt, getting into a wreck and a fight and needing to get in touch with his family. Dutton overheard the man give a partial telephone number and heard Tucker say she would call his family. Dutton — still in her bedroom — could tell from his voice that he had entered the home.

“Then he went like he was dialing the phone. I could hear a racket and it was like he was talking to somebody,” Dutton testified.

“I thought, well, he got in touch with his family. Then I heard (Tucker) say, ‘My husband is back in that room’ and then just a pop second and she went to screaming ‘Marie, Marie,’ and I knew he was doing something to her.”

Seconds later, Dutton testified, the attacker entered her room and stabbed her, too. He then ran out of the house.

Dutton that night described her attacker as a Black man, a “short chunky guy,” wearing a light-colored or “bluish white” shirt. But she wasn’t wearing her glasses at the time, and could not identify the man.

Tucker was not married, and her neighbors knew that. Myers was among those neighbors. He lived with his wife and four young children just across the street.

His oldest son, Robin LeAndrew Hood, was 11 at the time. He remembered Tucker as a nice woman who would sell ice to his father from the ice machine on her front porch.

Anthony, Myers’ wife at the time, talked about their connection to their neighbor.

“The one thing that I don’t understand,” she told AL.com. “The woman knew my husband. Why didn’t she say Rocky did it?”

Rocky Myers

In New Jersey, according to a psychological report filed in court, Myers attended a school for students with intellectual disabilities before dropping out in the 8th grade

Myers said during a phone interview with AL.com that he considered his brain to be slow and mentioned he gets frustrated when trying to learn new things.

“My brain just isn’t like that,” he said.

He said he prefers phone calls to letters. “I’m not a writer. I don’t write. I can’t spell a lot of things.”

Anthony said she had to give Myers a cash allowance because he didn’t know how to manage money; she handled all the finances, the paperwork, and household duties.

But Myers was a loving father, she said. She recalled Myers walking across town in fireman boots after a massive New Jersey snowstorm in 1979 so he could see their newborn son.

Hood returned to Moulton Street, walking along the sidewalk outside his childhood home as he spoke to AL.com in March. “There’s a lot of memories,” he said. He recalled Myers cooking a meal— hotdogs and macaroni and cheese, all mixed together. Hood shook his head and laughed.

“He tried his best,” Hood said said.

Myers held several jobs, working in factories and doing other manual labor. Anthony remembers her then-husband working at a nearby cotton gin in October 1991. He struggled to find work at times, she said, because of his eczema.

His condition was severe, Anthony said, and his skin often flaked off in pieces. Even the detective who interrogated Myers later recalled in court that “he did have real scale-y skin that looked bad on his arm.”

None of those pieces of skin were found at the crime scene.

On that night in 1991, Anthony, who had recently graduated from cooking school, worked an overnight shift at Shoney’s. She left the kids at home with her husband and wouldn’t get off work until 4:30 a.m. on Oct 5.

Hood said he remembers watching baseball that night with his father as his younger siblings slept. After Hood fell asleep, he said, his father carried him to his bunk bed.

“We were at home all night,” Hood told AL.com.

The investigation

On the night of the murder, police found footprints around the Tucker house, but none came from or were headed north toward Myers’ home.

The only thing police were able to identify as being stolen was a VCR – the cables were yanked out and still lying on the floor.

In the early days of the investigation, detectives zoomed in on a different man: A drug dealer at a nearby house named another alleged drug user as the one who traded Tucker’s VCR for crack cocaine.

A lookout at the drug house backed up the drug dealer’s story, telling police: “He got up there and he was sweating and shaking all over. He had a VCR under his right arm. At first I thought he was shaking from the cool air, he was wiping sweat and I could tell something wasn’t proper.”

Cops arrested and charged that first man.

But about a month later, after the governor offered a reward for information, new witnesses came forward, including a man who worked with the father of the first guy who police arrested. And, he said he saw Myers with the VCR.

Police reinterviewed the drug dealer and the lookout, and their stories changed, too. The same two witnesses now said Myers was the one who pawned the VCR for crack.

After the trial, the man who tipped police about Myers split the $5,000 reward with yet another witness, a man named Marzell Ewing.

About a month after Tucker’s murder, police interviewed Ewing. He also told investigators that on the night of Oct. 4, he was at the drug house and saw Myers come on the porch with a VCR. He was the only person at the house who knew Myers.

But he would later come to change his story, saying in court records that he never saw the VCR seller and only lied about Myers to get out of his own legal troubles.

Myers was in the system for an old auto theft charge, and police arrested him on a probation violation. They asked about Tucker, and Myers said he wasn’t involved. After more questioning, he said he found a VCR in the trash-strewn alley behind his home and traded it for crack.

But Det. Dwight Hale, who died in the years since working this case, testified that Myers changed his story about the VCR at least four times.

According to Hale’s testimony: “He said ‘I didn’t kill that woman, I didn’t steal that VCR or anything.’ At that point we said, ‘We are not asking you if you killed the woman. What we are trying to confirm with you is the fact that you sold the VCR… We are not saying you killed anyone.’”

“Myers thought about it a minute and said, ‘Well, I did sell the VCR, but I didn’t kill the woman.’”

Hale and his partner continued the questioning, as Myers slowly changed his answers to fit what was possible.

“He said he found it. He first started out saying he found it behind his house in the alley. When we got into it with him and said, ‘Well, when did you find the VCR?’ He said it was 40 minutes before the police ever arrived… We told him that was impossible because the VCR was stolen just prior to the police arriving because they arrived in less than a minute…”

“Myers hung his head and he thought for a minute and said, ‘Well, no, it was about 10 minutes before the police got there that I found it.’ I said, ‘That’s still a little early’ and then he backed up and said ‘I don’t remember what time I found it.’”

“I said, ‘Are you sure you found it in the alley’ and he said, ‘No, actually it was on top of a fence post in my backyard.’”

Those changes in his story would later lead some working on his defense to contend Myers may have not pawned the VCR at all, and just made up a story to please police because he thought it would allow him to go home.

No recordings exist of the police interrogation. The only recollection provided in court was one detective’s summary, handwritten after the interview.

At one point, the police said they told Myers they found fingerprints in the house and it would be better if he confessed “before we get the results.” But those prints did not match Myers, nor any other suspects.

And throughout the four-hour interview, Myers denied hurting Tucker or going into her home.

The trial

Watching from the jury box in 1994, Puckett said none of the witnesses seemed reliable. She said it was nearly impossible to keep everyone’s stories straight because their tales changed so frequently. “When they put out the reward for information, everyone was fingering everybody,” she said.

One witness claimed to have seen Myers with the VCR on the street, but a parking stub seemed to show they weren’t actually in the area at the time. Another person at the drug house said he saw Myers, but no one else could verify that witness was at the house that night.

No one could say what time or how many times Myers dropped by the drug house.

No physical evidence linked Myers to the attack. A partial palm print lifted from the Tucker home didn’t match Myers. And it didn’t match the man police first arrested, either.

The fingerprints on the VCR didn’t match Myers.

Hairs found on Tucker’s clothes were unlikely to have come from a Black person, evidence reports showed.

The other man, who was first arrested, was also a Black man. He testified, admitting he visited the drug house multiple times on Oct. 4, but told the jury neither time was after the murder and at neither point did he bring a VCR.

When contacted for this story and asked about the case, that man declined to comment. Public records show he had no criminal record before the arrest and has had no criminal charges since.

Myers also took the stand, saying that he smoked crack cocaine during the day and planned to meet up with friends to go to a nightclub. He didn’t wind up going to the club, though, after his friends left without him. Myers said he went home instead. That’s when, he said again, he found the VCR behind his home and later traded it for drugs.

Recalling his trial, Myers told AL.com: “I thought I was going home. I didn’t know that it would go this far. I really didn’t.”

The deliberation

During the sentencing phase, a jury recommended a sentence of life in prison without parole. Nine jurors voted for Myers to live, while three voted for death.

In the years since, Puckett has spoken out about why she voted to convict Myers even though she believed he was innocent. It was a strategic decision, she said, made along with others on the jury.

There were two or three people who wouldn’t budge on a guilty verdict. Puckett said if the trial ended in a hung jury and Myers was tried again, a second jury might send him to the electric chair.

So, she said, she and others made a deal — one that has occupied her mind for 30 years since: They would convict Myers of capital murder, but sentence him to spend his life behind bars.

At the time, Alabama had a law that allowed judges to override juries and impose a different sentence. And that’s exactly what Morgan County Circuit Court Judge Claude Bennett McRae did.

Puckett wasn’t at the sentencing—the jury had been dismissed. She got a call from a fellow juror with the news.

“I cried. It was a mix of anger and sympathy and remorse. I felt like I had just fed him to the wolves when we tried so hard not to do that,” said Puckett.

The missed deadline

Myers went through several legal teams over the years as his case wound through state courts.

When it was time to go to federal court, things started to fall apart.

Earle Schwarz, a lawyer from Tennessee, represented Myers at the time, after signing up through a national network of lawyers offering pro bono services. Myers legally had until March 15, 2003 to file a federal habeas corpus petition, according to court record

But, court records show, Schwarz never filed the petition. He stopped representing Myers, letting the clock run out.

After the 2003 deadline, the court sent the notice of resolution of his appeal to Schwarz, but not to Myers. “Schwarz now admits in an affidavit that he did not notify (Myers) of the result of the appeal and did not seek review in the Alabama Supreme Court, but, instead, ‘abandoned’ (Myers),” according to a 2007 recommendation and report from U.S. Magistrate Judge Michael Putnam.

Putnam noted the lawyer’s “abdication of responsibility,” according to an order from the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, and filed formal complaints against Schwarz with the Alabama and Tennessee Bar Associations.

In 2005, the Supreme Court of Tennessee publicly censured Schwarz over his handling of the Myers case.

Schwarz told AL.com that he did not want to comment for this story.

But despite the lawyer’s actions or inactions, Putnam ruled Myers “had no Sixth Amendment right to the effective assistance of counsel at that stage of his case,” and said missing the deadline could not be undone.

Schwarz later served as the vice president of the Tennessee Bar Association in 2016 and was elected as president of the Memphis Bar Association in 2018.

The witness recants

By the time Robin Myers found new counsel it was March of 2004, a year too late for his federal appeal. As Myers’ new legal team began to look into his case, one original accuser changed his story.

In 2004, Marzell Ewing admitted to Robin Myers’ lawyers that he lied about Myers being the seller of the VCR on the night of the crime.

Back in November 1991, police had picked up Ewing on an auto theft charge.

“After I named Mr. Myers as the seller of the VCR, (police) told me that I would not be charged with auto theft,” said Ewing in a 2004 affidavit. He said an officer “told me that he would take the stolen car that I had been driving and leave it by the side of the road.”

Court records show Ewing was not charged with auto theft.

“My trial testimony was not truthful,” Ewing continued in the affidavit. “I did not see who brought the VCR to the (house) that night.”

He said in the same affidavit that he only named Robin Myers because the drug dealer “told me that (Myers) had sold the VCR…” That man “had a lot of power over me at the time. He had a well-known relationship with the Decatur police and had protected me from the police in the past.”

Robin Myers’ new legal team of federal public defenders in Alabama offered Ewing’s story, arguments about Myers’ mental capacity and several other technical arguments. But ultimately, in 2009, U.S. District Judge Scott Coogler dismissed the case because of the missed deadline six years earlier.

Myers’ team appealed and in 2011 the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the state. The court called Schwarz’s actions “inexcusable abandonment,” but said Myers shared the blame, that he too did not “exercise reasonable diligence in pursuing his rights” or attempt to figure out what was happening in his case.

The appeals court also ruled that Robin Myers was competent enough to be executed. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case the next year.

After that denial, Myers’ legal team brought in a board-certified neuropsychologist to examine RobinMyers and the case.

“Rarely do I get a case with so much documentation on intellectual disabilities,” said Dr. Kristen Triebel, who examined Robin Myers in 2013 and determined he also had impaired reasoning and memory.

Triebel wrote in her report that Robin Myers is a “people pleaser” and that he “was very easily intimidated,” and vulnerable to suggestion during questioning. At points throughout the police interrogation, detectives noted that Myers broke down crying and asked to call his mother. Triebel said that behavior was more on the level of a child than a 30-year-old man with a wife and children.

She said Myers’ lifelong history of “truly impaired memory” meant he likely wouldn’t be able to pinpoint details of a particular night when questioned weeks later.

Triebel told AL.com that “the likelihood of him remembering an appeals court deadline — if he was told about it — is impossible.”

The only way out

Robin Myers said the day he went to prison, he stopped using drugs — he’s 29 years clean now. He said he spends his time encouraging other prisoners. “I’m still here, and trying to make the best of it.”

Because of Myers’ unique legal situation, a solution found through the courts is unlikely.

Gov. Kay Ivey is the only way out for Robin Myers, his legal team said. She has clemency powers that could let him out of prison or reduce his sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

“So, we know that clemency is a long shot for Rocky,” said his lawyer, Keeton, “and if we want to give him the best shot—we needed to start talking as soon as possible and as much as possible. And, that is what we have tried to do.”

“Also, once you know the injustices that happened to Rocky—you really just can’t keep silent.”

The judge who overrode the jury’s recommendation of life in prison has since died, along with the two main police investigators and several witnesses.

There are about three dozen other people on Alabama Death Row against the wishes of the juries that convicted them. And Alabama, despite recent challenges with executions, has more people awaiting execution on a per capita basis than any other state. For every 100,000 Alabamians, there are 3.3 people on death row – by far the highest rate in the United States.

Alabama has a history of putting to death people who claim to be intellectually disabled, executing at least five men in the past two decades who argued they shouldn’t be put to death following a Supreme Court ruling that executing people with intellectual disabilities violates the Eighth Amendment.

Police say that the trial court would have retained the fingerprint evidence from 1991. Scott Anderson, the Morgan County district attorney, didn’t respond to requests for comment on the prints or if they would ever reanalyze them.

Anthony stands by her ex-husband’s innocence, along with Robin Myers’ four children.

She hopes Ivey will save Myers’ life. “If they don’t let him go, they don’t need to kill him… They know it was shambles in the first place. Just let him live.”

Puckett, the juror, is also working to get the governor’s attention. When Myers’ new lawyers called, Puckett told her story. “I thought about that man every day,” she said. “Every day of my life.”

Robin Myers had an execution date set in the summer of 2015, but avoided it after opting into legislation over the state’s use of drugs in its lethal injection protocol. In 2018, he signed a paper electing to die by nitrogen asphyxiation instead.

The state claims the new method will be ready sometime this year. Since he is out of appeals and once had an execution date set, Myers could become the first scheduled to die by the new method.

And yet, he hasn’t given up hope for a future.

“I gotta stay strong,” said Myers in a call from prison. “I can’t be in here, you know with my bottom lip poked out. I don’t want to live like that.”

Robin Myers said he looks to a photo of roses, pasted to the wall of his prison cell, for hope he will one day see the outside world again.

“I’ve got a fake turtle on my floor. I’ve got a picture of roses on my wall that I see every day and I talk to this paper turtle for my pet, you know, and I do that just to keep me sane,” he said.

“And I believe I will smell the roses.”