James Were was sentenced to death by the State of Ohio for a prison murder

According to court documents during the Lucasville Prison Riots James Were would participate in the murder of prison officer Robert Vallandingham

James Were would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death

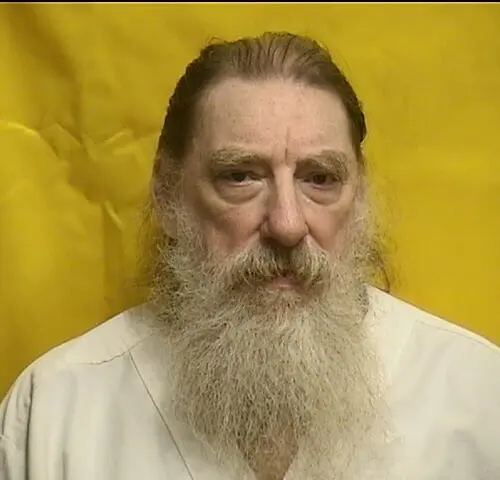

James Were Photos

James Were Now

Number

A173245

DOB

01/20/1957

Gender

Male

Race

Black

Admission Date

04/15/1983

Institution

Ohio State Penitentiary

Status

INCARCERATED

James Were Case

¶ 6}As the takeover began, a group of masked inmates entered the L-1 cellblock where Vallandingham was stationed. Vallandingham had locked himself into the officer’s bathroom near the front of the L-1 cellblock. Several inmates turned over a metal desk and started banging that desk against the bathroom door. Inmate Steve Macko identified Were as one of the inmates near the bathroom at this time. Eventually, Vallandingham was removed from the bathroom. {¶ 7}Were, Sanders, and Reggie Williams, another Muslim gang member, then took Vallandingham down the corridor to the L-6 cellblock. Vallandingham was put into the L-6 shower where his hands were cuffed behind his back and a sheet was placed over his head. Vallandingham was later moved to a cell in the L-6 cellblock. {¶ 8}Organized negotiations between the authorities and the inmates began on the second day of the riot. Additionally, on the second day, the Ohio State Highway Patrol (“OSP”) installed listening devices in the large tunnels underneath L-Block. Shortly thereafter, the FBI supplied more sophisticated listening devices, which were placed in crevices at ten locations underneath L-Block. Authorities then listened and recorded inmate conversations, referred to as the “tunnel tapes,” during the duration of the riot. A total of 591 “tunnel tapes” were created. Also, on the second day of the riot, the water and power were turned off inside L-Block. {¶ 9}On April 14, the public information officer for the Department of Corrections responded to media questions about inmate threats. She stated that there had been threats and that they were a standard part of the negotiations. The inmates, who were following the news on battery-operated televisions and radios, were upset by these comments and felt that the authorities were not taking them seriously. {¶ 10}During a meeting on April 15 that was recorded on tunnel tape 61, Were and other inmate leaders discussed killing one of the hostages to show the authorities that they meant business. Were, who described himself as a hardliner, urged others to take a firmer stand during the negotiations. Were said that the water and power must be turned back on. He continued, “We give [the authorities] a certain time * * *. If it’s not on in a certain time, that’s when a body goes out.” Were also said, “[F]rom this point on we’re turning it over to the hardliners.” {¶ 11}Before the April 15 meeting concluded, Were and the other inmate leaders voted to kill a corrections officer if their demands were not met. The Muslim inmates decided that Vallandingham would be killed because he had seen them kill another inmate at the beginning of the riot. After the meeting, Were stated, “I’ll do it, I’ll do it, I’ll take care of it. The hardliners is taking over. I’ll take care of it.” {¶ 12}Around 9:00 a.m. on April 15, Skatzes had a telephone conversation with state negotiators. Skatzes said, “I cannot stress to you * * *. If

you don’t turn it on, it’s a guaranteed murder. * * * That’s the end of it. Do your thing at 10:30 or a dead man’s out there.” The inmates’ demands were not met. {¶ 13}During the riot, inmate Thomas Taylor was locked in a cell in the L-6 cellblock. On the morning of April 15, Taylor saw Were and another inmate remove Vallandingham from his cell and take him to the end of the L-6 cellblock. Around the same time, inmate Sherman Sims walked past the L-6 shower area. Were was standing at the shower door and looking into the shower. Were noticed Sims and asked what he was doing there. While this exchange took place, Sims looked into the shower and saw a man with something over his head being strangled with a rope by two people. He also saw one of them “putting a bar to [the man’s] throat.” {¶ 14}Were told Sims that he would have to help carry the body out of the prison. Were directed the inmates to wrap the body in sheets. At 11:10 a.m. on April 15, Sims and three other masked inmates carried Vallandingham’s body from the prison and into the recreation yard. {¶ 15}After the body was taken into the yard, Reginald Williams, a Muslim inmate, saw Were talking to Cummings while Cummings was on the phone with the state’s negotiator. Were said, “You can come get your boy * * * he’s out there, and you didn’t take us serious. And from this point on, * * * you’ll take us serious.” {¶ 16}At 12:10 p.m. on April 15, a SWAT team recovered Vallandingham’s body from the recreation yard. {¶ 17}On April 17, Were and other inmate leaders had a meeting to discuss the progress of negotiations. This meeting was recorded on tunnel tape 32. Were argued that the hardliners should control the negotiations. During the meeting, Were said, “If everybody can recall when we first started to see improvement in here, when we sent an officer out there, that is when we started to get to see some improvement. * * * When that officer went out there, that body went out there, that is when they began to see that we is serious, because all along they said that we are not serious * * * .” {¶ 18}Were continued, “I am putting it just like this * * * if we have to throw another body, it will let people know the hardliners will put their foot down * * *. I don’t give a damn you understand if some of the hostages die slow, or die at all, if I have to die, or we have to die, so I feel then if I cut off a man’s fingers, I will cut the man’s hand off and go out there and say now, I am going to let you know we ain’t interested in killing your hostages, they’ll die slow, since you all want to play games. We is for real about what we is about, man.” {¶ 19}A short time later, Were said, “[T]hey only respect firmness. * * * I don’t give a damn if it has to be on national TV, for them to see me personally, cut one of them dudes hands off and give it to them and spit it out of my mouth for them to know how serious I am about what we believe in. I don’t care nothing about no electric chair, I don’t care nothing about no other case * * * we got what they want and they got what we want.” {¶ 20}The riot ended on April 21, 2003, when the remaining hostages were released. Investigators then began interviewing witnesses and collecting evidence from inside the prison. No useful physical evidence linking any person to Vallandingham’s murder was ever recovered.

https://law.justia.com/cases/ohio/supreme-court-of-ohio/2008/2008-ohio-2762.html