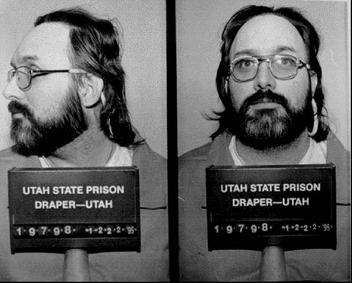

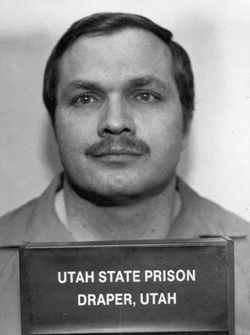

Taberon Honie was executed by the State of Utah on August 8 2024 for a murder committed in 1998

According to court documents following a breakup with his girlfriend Taberon Honie would break into the home of his ex girlfriends mother, Claudia Benn, and proceeded to slash the woman several times before slitting her throat and stabbing her to death

Police would arrive at the murder scene and find Taberon Honie in the garage with blood underneath his fingernails. Honie would admit to the brutal murder

Taberon Honie would be convicted and sentenced to death

On August 8 2024 Taberon Honie would be executed by lethal injection

This is the first execution in Utah since 2010. The majority of inmates on Utah death row have requested to be executed by firing squad including Troy Kell

Taberon Honie Execution

A death row inmate in Utah set to be executed on Thursday maintains that he never meant to murder his ex-girlfriend’s mother, saying he has always taken responsibility and is sorry for the life he took 25 years ago.

Taberon Honie, 48, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection for killing 49-year-old Claudia Benn, a substance abuse counselor for the Paiute Tribe who was killed on July 9, 1998, at her home in Cedar City in southwestern Utah.

If the execution proceeds as scheduled, he will become the 12th inmate to be executed in the U.S. this year and the first executed in Utah since a 2010 execution by firing squad. It will also come just two days after an execution in Texas.

“Yes, I’m a monster,” Honie told the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole last month. “The only thing that kept me going all these years, the only thing I know 100%, this would never happen if I was in my right mind … I make no excuses.”

The board denied his request for a reprieve.

As his execution day approaches, USA TODAY is looking back at the crime, who Honie is and what led him down a path that ended in a woman’s horrific death.

On July 9, 1998, Taberon Honie was drunk and fighting over the phone with girlfriend Carol Pikyavit, who was staying at her mother’s house along with the daughter she shared with Honie, according to court records. At one point, records say, Honie threatened to kill everyone in her home and take the couple’s daughter if Pikyavit didn’t make time to see him, records say.

Not taking the threat seriously, Pikyavit left the home and headed to work.

Honie headed to the house, saying he had planned to sleep under the porch until Pikyavit came home. But as soon as he arrived, he began arguing with Pikyavit’s mother, Claudia Benn, who was babysitting her three granddaughters.

Taberon Honie told police that Benn started the argument and was calling him names through a sliding glass door before he snapped, broke through the door and went inside, saying he just wanted to scare Benn.

Benn had grabbed a butcher knife but was overpowered by Honie, who grabbed the knife and brought it to her throat, court records say. Honie says the two of them both tripped while the knife was at Benn’s throat and that she fell on the blade.

When police arrived shortly after, Honie − covered in blood − emerged from the home and said he had “stabbed and killed her with a knife,” court documents say. Benn was found face down in the living room, with numerous “stabbing and cutting wounds” to her neck and genitals, according to court documents.

All three grandchildren were found at the home with varying degrees of blood on their clothes and body. There was also evidence that one of Benn’s granddaughters was sexually abused at some point, court documents say.

Honie was arrested, charged and convicted of aggravated murder.

Honie was raised with five siblings in First Mesa, a village on the eastern side of the Hopi Reservation in northern Arizona, and is considered Hopi-Tewa. His childhood was marked by “neglect, violence and chaos,” according to a commutation petition filed in June seeking to have Honie’s death sentence thrown out in favor of life in prison.

Life on the mesa was “extremely difficult,” as the family of eight survived without access to basic resources like running water or toilets for nearly a decade, the petition says.

“We had no recreation center, no after-school activities, nothing,” Honie says in the petition. “We lived at a poverty level below the city slums. We all had a view that, ‘I will never amount to anything. I will never be able to leave the mesa, so what is the use?’”

Honie and his siblings often were left to fend for themselves, with the older children starting fires to cook or warm the house since Honie’s parents were always “absent, drinking and fighting,” the petition says.

Honie began to act out at the age of 10, turning to alcohol and drugs after falling in with the “wrong people,” and later stealing things to obtain booze and drugs. His substance abuse problems continued into adulthood until his arrest.

Honie has also grappled with bouts of depression, getting a formal diagnosis in 2009 following various suicide attempts.

Honie’s traumatic childhood, brain damage, long-standing substance abuse and extreme intoxication all had a “synergistic effect,” impacting his ability to control his judgment and behavior on July 9, 1998, the commutation petition says.

“Honie also inherited generations of trauma from his parents, extended family, and his Hopi-Tewa community, which is referred to as intergenerational trauma,” the petition says.

Honie may have done a “horrible” thing but he has paid for it by serving nearly 25 years on death row, according to the petition. And even if his death sentence is thrown out, he will continue to pay by spending the rest of his life in prison

“Mr. Honie does not have to be executed and is worthy of mercy,” according to the commutation petition, which says Honie has led a positive and productive life in prison, earning a high school diploma, learning a trade (plumbing) and staying close with family.

Honie’s execution would only “create more pain,” devastating his daughter Tressa and his granddaughter Alana, who have spent years worried about “Mr. Honie and his circumstances in the prison.”

“His family loves him very much,” the petition says. “His family has suffered much throughout their own lives and losing Mr. Honie to an execution would be devastating to them.”

Utah Attorney General Sean Reyes argued against Honie’s clemency petition, citing “Honie’s horrific acts, their life-long impact on Claudia’s family and her tribal community.”

He said combined, they all demonstrate a “failure to own up to the terror and gravity of his conduct.”

One of Honie’s daughters, Benita Yracheta, told USA TODAY that she’s feeling relief that she can soon put her mother’s death behind her, saying that justice for her mother is “finally happening.”

“I had told them that I had cried for this man that killed because now that he knows his death date, he’s trying to throw everything out there to stop it,” she said. “My mom, she never knew her death date. She didn’t know she was gonna die that night, but I know that he needs to end it.”