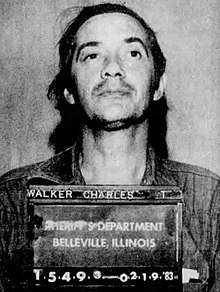

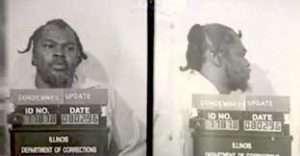

Charles Walker Executed For 2 Illinois Murders

Charles Walker was executed by the State of Illinois for a double murder According to court documents Charles Walker would rob Kevin Paule, 21, and his fiancée Sharon Winker, 25. The young couple who were fishing while the robbery occurred would be fatally shot Charles Walker would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death Charles […]

Charles Walker Executed For 2 Illinois Murders Read Post »