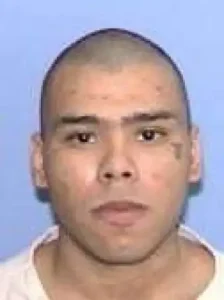

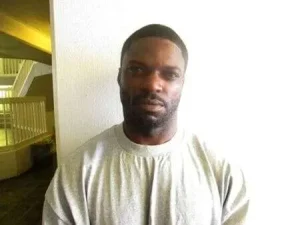

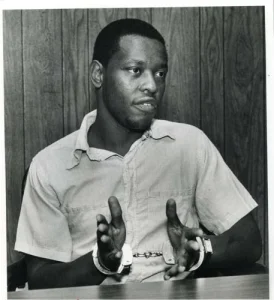

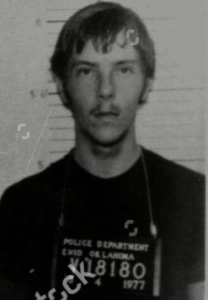

Emmanuel Littlejohn Executed In Oklahoma

Emmanuel Littlejohn was executed by the State of Oklahoma for a murder that was committed in 1992 According to court documents Emmanuel Littlejohn and Glenn Bethany would enter a convienence store and in the process of the robbery the store manager Kenneth Meers would be shot and killed Emmanuel Littlejohn and Glenn Bethany would be […]

Emmanuel Littlejohn Executed In Oklahoma Read Post »