Joseph Jernigan was executed by the State of Texas for the murder of Edward Hale

According to court documents Joseph Jernigan and an accomplice would break into the home of Edward Hale, 75, when the homeowner would discover the two men inside of the home he would be beaten to death

Joseph Jernigan would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death

Joseph Jernigan would be executed by lethal injection on August 5 1993

Jernigan would give his body to science and after his execution his body would be sectioned Visible Human Project and the University of Colorado School of Medicine by Dr. Vic Spitzer and associates

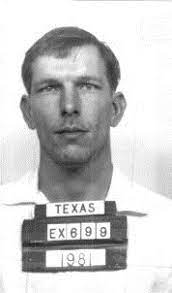

Joseph Jernigan Photos

Joseph Jernigan Case

Alive, he wasn’t much. Joseph Paul Jernigan spent many of his 39 years as drug abuser, alcoholic, robber, killer. In 1993, the state of Texas injected him with lethal chemicals and took his life.

“I’m glad it’s over,” Wilmer Hale, a nephew of the 75-year-old man Jernigan killed during a 1981 robbery, said on the night of the execution. “Maybe this will be the end.”

But the conclusion of Jernigan’s mortal existence sent his body on a most unusual odyssey that has made him into something life couldn’t–a productive member of society.

His corpse has been frozen, sliced into 1,871 1-millimeter cross-sections, photographed, digitized and put on the Internet for all to see. He has become a federally funded project called “The Visible Human”–medical tool extraordinaire and ultimate guinea pig.

“How do you study an orange? By cutting it in half. So it made sense with a human being,” said Victor Spitzer, a University of Colorado anatomist whose team cut up and photographed Jernigan’s corpse.

Reduced to seven gigabytes of data–about 20 times as much as can be stored on the average personal computer these days–Jernigan comes almost alive.

Dr. Michael Ackerman, a biomedical engineer at the National Library of Medicine who initiated the $1.4-million project, traces it to mid-1987, when a University of Washington anatomist showed him a computer monitor with a rotating picture of a skull.

When a joystick glided a cursor across the skull and clicked, it opened up to show the brain inside.

“He said to me, ‘This is the way anatomy should be taught,’ ” Ackerman said.

Over the next months, Ackerman found similar projects: a physiologist working on a kidney in Minnesota, a Washington doctor digitizing a torso. But each project was being done on different machines.

“It occurred to me that we needed not a bunch of these machines for different parts, but one to do it from head to toe,” Ackerman said.

Representatives from eight medical schools met in mid-1988 and proposed the full-body approach. But many worried that existing technology–this was still a world of tortoise-speed modems and hard disks more cramped than a Manhattan studio apartment–couldn’t support the project.

A Hollywood special-effects guru was sitting in on one discussion, though. And, movies being bigger cash generators than research projects, he already had a machine that could do the job.

“He said, ‘Trust me. Do it. By the time it’s done you’ll be ready to deal with it,’ ” Ackerman said. “And he was right.”

It took 2 1/2 years from the project’s launching to find the right body. After all, most people who die–either by old age or violence–don’t leave prime human specimens behind.

At 12:15 a.m. on Aug. 5, 1993, Jernigan was executed in Huntsville, Texas. He had donated his body to science, and science moved quickly: Seven hours later, the cadaver arrived at Spitzer’s lab, where it was X-rayed and scanned.

After that, Jernigan was frozen and his legs linked by gelatin so that slices would be symmetrical. A similar process fastened arms to abdomen.

It took nine painstaking months, about 50 slivers a day, before Jernigan was entirely sliced away. The National Library of Medicine organized the photos, put them on the Internet–and Jernigan became medicine’s first virtual human canvas.

Now, with the right software, the slices can be stacked up on-screen to recreate Jernigan’s body–or any particular part of it–in 3-D.

Jernigan, who had exercised and pumped iron for years in prison, contributed a well-developed body that–though it lacked the appendix and one testicle–was a near-perfect teaching specimen.

Which is exactly what Dick Cozza is doing today. The health and physical education teacher at Smoky Hill High School in Aurora, Colo., uses The Visible Human to let his students “see a body in a way that has never been seen before.”

“Instead of dissecting a frog, they can dissect a human being on the Internet. And there’s no smell and no blood on your hands,” Cozza said.

“We sit back and talk about fat and marbleizing and how fat gets into the human tissue. And when you pull up this picture and you have that nice piece of red meat staring you in the face and it’s a human piece of meat, it makes an impression–and they learn.”

More than 300 people worldwide–artists, entrepreneurs, students, doctors–have obtained free licenses for a higher-quality scan of the data. A group in Japan displaying Leonardo da Vinci’s prints of the human body wants to put the corresponding parts of Jernigan alongside it.

Knowledge Adventure, a San Diego educational software firm, used the Visible Human last year to give its $35 “3-D Body Adventure” CD-ROM an impressive software upgrade–from anatomical drawings to real pictures.

“We wanted to democratize this information,” said Dr. Paul Chesis, a UCLA radiologist who engineered the software. In it, The Visible Human pictures allow a user to point, click and call up the exact organs or body parts desired.

Spitzer sees beyond such uses. Future software, he predicts, will allow doctors to use the virtual Jernigan as a surgical simulator much as pilots use a flight simulator. They will be able to age and de-age him, amputate an arm, add a torn ligament, introduce a heart attack or throw in a bullet wound.

Even sooner, Ackerman says, will come software that simulates magnification to a molecular level by zooming in on close-ups of The Visible Man and jumping to another database.

Spitzer even acknowledges that an innovative video game manufacturer could produce a frighteningly real game, “Mortal Kombat”-style, from the data.

“There’s no reason why someday you couldn’t shoot this man for entertainment reasons,” Spitzer said. “That’s disgusting. But it will probably happen soon.”

Inevitable, perhaps, is the project’s next step–The Visible Woman, the corpse of a 59-year-old Maryland woman who was sliced three times finer than Jernigan last September. A Visible Child may ultimately join them, Ackerman says.

So Joseph Jernigan, a man whose actions ended a life and damaged uncounted others, has become, for eternity, a subject to be virtually poked, prodded and studied in the name of science.

“I think da Vinci would be proud,” Ackerman said. “This is everything that he stood for–art and science combined. I used to talk about ‘Fantastic Voyage’ on disk. And it was pretty fantastic then. But it’s not so farfetched anymore.”

The Visible Human Project is located on the World Wide Web at https://www.nlm.nih.gov/extramural– research.dir/visible– human.html