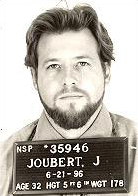

John Joubert Executed Nebraska Serial Killer

John Joubert was a serial killer who was executed by the State of Nebraska for three murders According to court documents John Joubert would murder 11-year-old Richard “Ricky” Stetson in Maine in 1982. In 1983 Joubert would murder Danny Joe Eberle, 13, and later the same year he would murder Christopher Walden, age 12, both […]

John Joubert Executed Nebraska Serial Killer Read Post »