Archie Dixon and Timothy Hoffner were sentenced to death by the State of Ohio for the murder of Christopher Hammer

According to court documents Archie Dixon and Timothy Hoffner would kidnap Christopher Hammer and bring him to a remote location where he was buried alive

Archie Dixon and Timothy Hoffner would then steal all of the victims belongings and emptied out his bank account

Archie Dixon and Timothy Hoffner would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death

Archie Dixon Photos

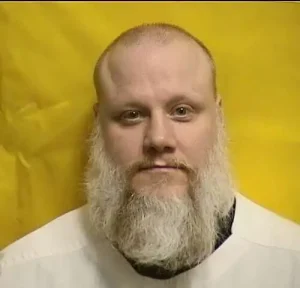

Timothy Hoffner Photos

Archie Dixon And Timothy Hoffner FAQ

Where Is Archie Dixon Now

Archie Dixon is incarcerated at Chillicothe Correctional Institution

Where Is Timothy Hoffner Now

Timothy Hoffner is incarcerated at Chillicothe Correctional Institution

Archie Dixon And Timothy Hoffner Case

Christopher Hammer was reported missing by his mother, Barbara Hammer, on or about September 30, 1993. Mrs. Hammer also reported that, shortly before his disappearance, her son had been living in a home at 3624 McGregor Lane with Archie Dixon, Kirsten Wilkerson, and appellant. On or about October 25, 1993, Barbara Hammer informed Detective Ron Scanlon of the Toledo police division that her son’s friend had reported to her that he saw Christopher Hammer’s car at a used car lot in Sylvania Township. On November 8, 1993, Detective Scanlon displayed a photographic line-up to salesmen at the car lot, and two of the salesmen identified Archie Dixon as the man who sold them Christopher Hammer’s car. Officers then obtained a search warrant for the home on McGregor Lane and an arrest warrant for Archie Dixon for forgery. A group of approximately eleven officers, some uni formed, some not, executed the search warrant at approximately 11:00 a.m. on November 9, 1993. Because appellant’s first two assignments of error are directed toward this search, we will recite in detail the facts relating to the search. These facts are derived from the testimony given at the hearings on two motions to suppress evidence.

When Lieutenant Charles Hunt of the Toledo police division entered the family room of the McGregor Lane home on the day of the search, he found appellant laying on a couch with a blanket over him. It appeared to Lt. Hunt that appellant had been sleeping. With his gun pointed in the air, Lt. Hunt ordered appellant to get off the couch and to put his hands in the air. Lt. Hunt pulled the blanket off with his left hand, holstered his gun, and patted down appellant. Lt. Hunt instructed appellant to sit in a chair in the family room. Upon appellant’s request, officers permitted appellant to smoke cigarettes while the officers searched the room. Lt. Hunt testified that appellant never asked to eat or to use the restroom. According to Lt. Hunt, officers asked appellant if he knew where Christopher Hammer was or where Hammer’s property was. Lt. Hunt also testi fied that officers told appellant that if he was not involved in Hammer’s disappearance he had nothing to worry about. At this point, appellant denied having knowledge of Hammer’s whereabouts.

Both Lt. Hunt and Detective Robert Leiter testified that during the search, while appellant was seated in a chair in the family room, appellant asked to speak with them. Appellant then began to give the officers information about Hammer’s disappearance. Appellant told the officers that, one day some weeks earlier, Dixon had asked appellant and a friend to give Dixon a ride. They drove to a parking lot behind an apartment complex off Alexis Road, and appellant saw Christopher Hammer’s car there. Dixon got into Hammer’s car, telling appellant and his friend to follow him. Dixon drove to a car dealer on Central Avenue and sold the car. Appellant and the friend then took Dixon to a bank, and they then drove him back to the McGregor Lane home. Appellant also told the officers that sometime later he had been driving around with Dixon, and he asked Dixon if he knew where Hammer was. According to Lt. Hunt, appellant stated to him that Dixon pointed toward a wooded location in the area of Secor and Alexis. Appellant asked Dixon whether Hammer was walking around in the woods, and Dixon replied that Hammer was, indeed, in the woods but that he was not walking around. Accord ing to appellant, Dixon said that he had gotten into an argument with Hammer and that he “took care of him.” Appellant had not been given his Miranda rights at this time, and the officers both testified that they considered appellant merely a witness at this point. At no time during the search was appellant restrained or restricted in his movement.

At some point during the search, Detective Scoble of the Toledo Police Division approached appellant in the family room of the home and asked appellant who owned the Firebird parked in the driveway. Appellant stated that he (appellant) owned it. Detective Scoble testified that he asked appellant for his permission to search the car, and appellant consented to the search. Appellant and Detective Scoble proceeded to the car, where they were met by Detective Scanlon. Before the detectives searched the car, they presented a consent form to appellant, which appellant willingly signed. Detectives Scoble and Scanlon testified that appellant read the form before signing it, that he appeared to understand it, and that they did not coerce him or issue any threats or promises to induce appellant to sign the form. Appellant was not restrained in any fashion during the search of his car. After obtaining appellant’s oral and written consent, Detectives Scoble and Scanlon searched his car. They seized, among other things, a pair of tennis shoes from the trunk.

After appellant made the above-described statements to the police, and after the police searched appellant’s car, Detective Leiter and Lt. Hunt asked appellant if he would go downtown with them to make a statement. Appellant agreed. Again he was not restrained in any way, and his freedom of movement was not restricted. Detective Leiter testified that, on the drive downtown, he stated to appellant that the police were going to have to search the entire wooded area that appellant had indi cated was the grave site, and if he (appellant) had any other information, that information would be helpful to the police. Appellant stated that he had no other information. Detective Leiter testified that he asked appellant if he had any involvement in the disappearance of Hammer, and appellant responded that he did not. When Lt. Hunt had driven nearly the entire way downtown, appellant asked him to pull the car over. When Lt. Hunt pulled the car over, appellant stated that he had to talk to the officers about something. According to Detective Leiter and Lt. Hunt, appellant then stated that Dixon had shown him where he had buried Hammer. Appellant also stated that the day after Dixon had shown him the grave site, he (appellant) returned to that spot in the light of day and observed that the ground looked like it had been dug up and filled back in. He agreed to take the officers to the grave site.

The officers drove toward the area of the grave site and appellant directed the officers past a couple of paths before identifying one as the right path. Though several other officers were in tow at this time, appellant stated that he only wanted Hunt and Leiter with him. Appellant walked quickly down the path ahead of the officers and was, at certain times, outside the officers’ sight. After appellant identified the grave site, Detective Leiter took appellant back to the car. Subsequently, Hunt returned to the police car as well, and after speaking with Detectives Leiter and Scanlon, he learned that appellant had agreed to go downtown to make a statement as to the information he had provided to the officers. Appellant was not restrained at this time, and he had not, at this time, been read his Miranda rights.

At about 3:30 p.m. on November 9, 1993, appellant accompanied the officers to the safety building to make a state ment. He was not under arrest. Nevertheless, Detective Leiter advised appellant of his rights pursuant to Miranda v. Arizona (1966), 384 U.S. 486. Detective Leiter testified that, with a tape recorder running, he presented a waiver of rights form to appellant and went over the entire form with him paragraph by paragraph. Detective Leiter asked appellant if he was under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and appellant replied that he was not. At the conclusion of this exchange, appellant confirmed that he understood his rights and wished to give a statement. He did not want a lawyer. He then gave a taped statement to the police, never asking during the process to end the statement or to get a lawyer. After taking appellant’s statement, Detectives Leiter and Kulakoski drove appellant back to the home on McGregor Lane, where he gathered his belongings and proceeded to his mother’s house in Perrysburg, Ohio.

After taking statements from Archie Dixon (who by this time had been arrested and was being held in the county jail) and from Kirsten Wilkerson, and upon the advice of the county prose cutor’s office, officers obtained a warrant for appellant’s arrest. He was arrested without incident at his mother’s home shortly after midnight on November 10, 1993.

After his arrest, Toledo police officers took appellant to the downtown police station. Appellant was placed in front of Detective Leiter’s desk and Detective Leiter sat behind his desk. Detective Kulakoski was the only other person present in the room. Appellant’s handcuffs were removed. He was given a beverage and offered a chance to use the restroom. Appellant was again advised of his Miranda rights and, according to Detective Kulakoski, appellant initially stated that he did not wish to give a statement. Subsequently, however, appellant did give a taped statement. Before the statement began, Detective Leiter, on tape, reviewed the waiver of rights form with appellant, again reading it paragraph by paragraph, and appellant stated that he understood his rights. He then gave a statement confessing to his involvement in Christopher Hammer’s death.

On March 1, 1994, appellant moved to suppress the statements he made to the police on November 9, 1993 and in the early morning hours of November 10, 1993. On September 30, 1994, he also moved to suppress evidence of the tennis shoes recovered during the search of his car on November 9, 1993. In an opinion file-stamped January 23, 1995, and following hearings on April 12, 1994, April 28, 1994, April 29, 1994, May 3, 1994, June 1, 1994, and January 5, 1995, the trial court denied both motions.